Grandfather’s Polish Passport

Grandfather’s Polish Passport

Benjamin J. Bax

Growing up, I always knew that after arriving to the Unites States, my grandparents had a hard life: not knowing the language, working first on farms then in factories, facing discrimination and being denigrated as “Polaks.” My mother was the first and only child of her family born in the US when my grandmother was 40 and my grandfather was 42. Dziadek, Józef Palkij, died a month before his 71st birthday when I was only 16 months old. The memory I have of him was formed from family photos in which he is a frail old man in his late 60s. Babcia, Kazimiera (Mielczarek) Palkij, died when I was six but I have many memories of her, especially speaking a few words of Polish with her (mleko, daj mi buzi, etc.) because she did not speak English. Until I was probably around ten, I believed that their actual names were dziadek and babcia, and to this date we simply refer to them as such.

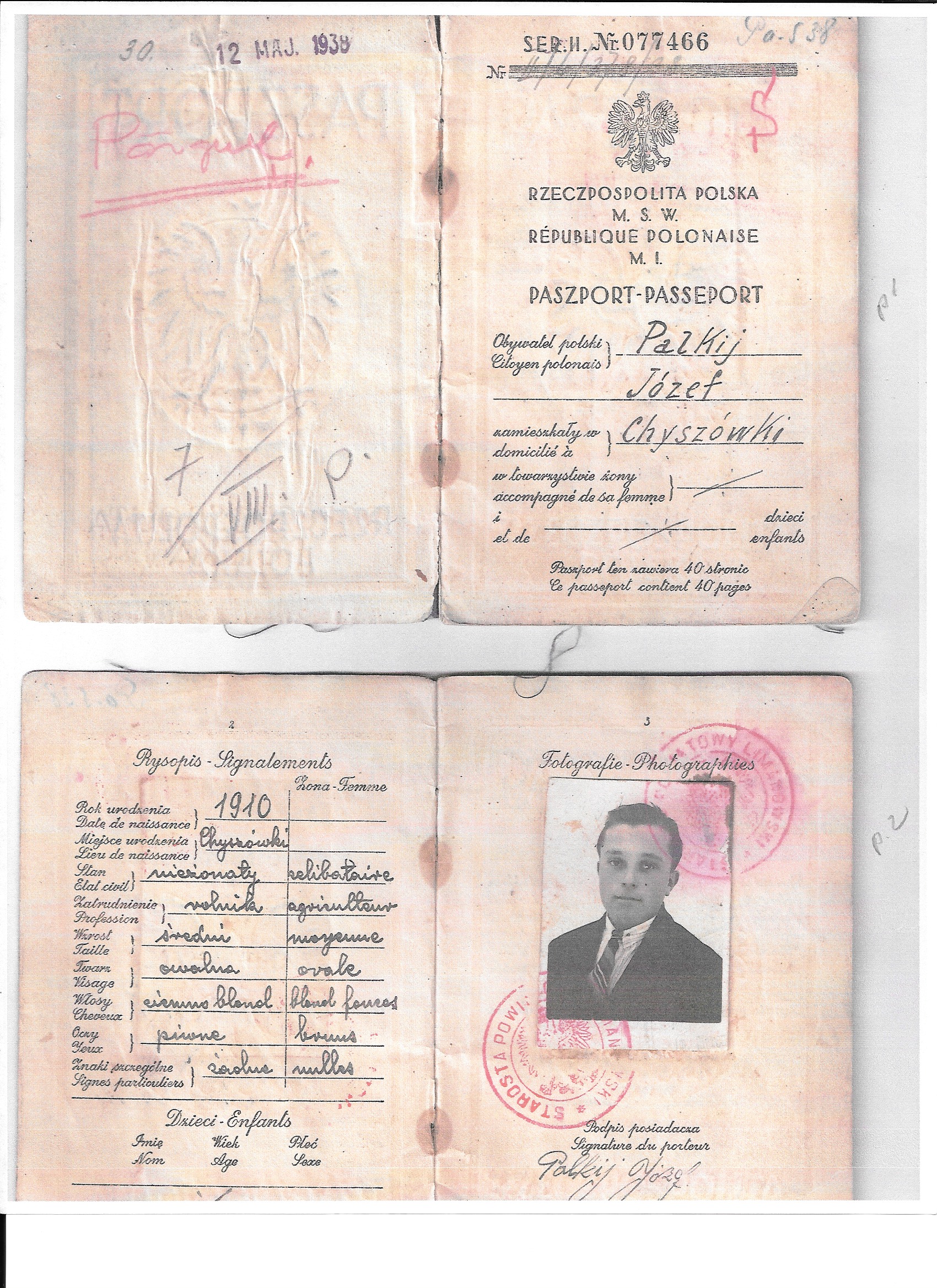

When I was in high school my mother’s sister Mary gave our family 8x10 portraits of both dziadek and babcia. I remember after opening the box and removing the portraits, my mother shed a few tears, kissed her fingers, and then placed those fingers on the forehead of first my grandfather and then my grandmother. These were copies of photos from their Polish passports which were issued by the Polish government in 1938 with first stamps of entry to Riga, Latvia in May 1938. It was the first time that I had ever seen my grandfather as anything but an old man who lived a hard life. The contrast of my mental image of dziadek compared to this vibrant professional young man in a suit was amazing. Just as children have trouble perceiving their parents as being anything but a parent, my grandfather had always been an old man to me until this point in time. I remember when one of my friends came over after we had first displayed these portraits and almost after immediately looking at the portrait of dziadek he said, “Dude, that’s you!” noting the resemblance. My heart swelled with pride at hearing this and I felt connected to my grandfather and my Polish family in a way that I hadn’t prior to this.

My dziadek, Józef Palkij was born in Chyszówki in and baptized in Jurków in 1910 in what is today’s Lesser Poland. Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, my grandparents were working in Latvia but returned to Poland after the fighting commenced. When they arrived in Poland, they were met by the gestapo at the train station and taken to Mecklenburg. My grandparents worked on various farms as forced laborers during the war, but I do not know exactly where the farms were in Germany.

My aunt recently shared a copy of dziadek’s Nazi “Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer” in which he is emaciated wearing clothes branded with a "P" and appears to have aged more than a decade, in the span of only two years. The juxtaposition of the two photos creates a stark contrast between the hopeful aspirations of youth, and the defeated, hollow man who suffered at the hands of the murderous Reich, emblematic of many Poles and Poland herself during the war.

My grandparents did not return to Poland after the war due to the newly formed communist government. Dziadek and babcia first were at a displaced persons camp in Kempten, Germany. He served as deputy camp leader for the Polish DPs and received a letter for his service stating that he was “fair and moral.” After the IRO dissolved this camp in 1946, they were relocated to the displaced persons camp in Altenstadt, Germany. They stayed there until leaving for America during the Spring of 1951. While at this DP camp he was an alderman in the camp court, served on the camp council, and was a block leader. Aside from what I have learned through these documents, all I know of camp life are anecdotal stories from my Aunt Helen such as procuring rations in an old coffee can.

He and his family traveled to the United States aboard the U.S. Navy transport General S.D. Sturgis during the Spring of 1951. The ship sprung a leak and the passengers bound for New Orleans had to change ships in New York City. My aunt Mary was three and a half at this time and was photographed on the boat by a reporter investigating the story about the leak. I had always thought that this photo was published and held in the family records, but after speaking with my mother, who also consulted my aunt regarding a copy of this, it appears to be something of family legend. The New York Times article did not include a photo of a cute three and half year-old Polish refugee. After entering the country through the port of New Orleans they settled on a farm in Kansas outside Kansas City.

The portrait of my dziadek from his passport is still displayed at my parents’ house in their living room alongside the portrait of my babcia from her Polish passport. They are displayed next to other important family pictures such as those of my parents’ wedding and 40th anniversary and my mother’s college graduation from obtaining her bachelor’s degree right before she turned 60. This photo served as my only connection to him aside from early memories, family stories, and my middle name. As displaced persons, my grandparents did not have many material possessions to bring with them to the United States other than their official government issued identification and documents. They cherished these along with their Polish citizenship and never became citizens of their new country.

I grew up in Oklahoma away from family and without any Polish community so my mother and her family stories were my only connection to my heritage. This portrait not only created a bond between me and my mother’s family and my Polish heritage, but also awakened an intellectual curiosity within me for more information about not only my family history but of the plight of Polish DPs. I am an attorney by training, but changed careers and became a high school social studies teacher and taught both AP World History and AP European History. I have completed a couple graduate history courses at the local college and wrote two papers about Polish DPs. As I both learn snippets of information from family stories or documents, with each question answered multiple new ones are presented. To this day, I cannot fathom losing 11 years of the most promising and productive years of life to forced labor, refugee camps, and having one’s homeland destroyed by one invader and then corrupted by another.

This photo has taken on new meaning for me recently because I am trying to establish my Polish citizenship by descent. The passport from which the portrait was created will serve as the basis for my application. I shared this with my twin sons who are both proud to be Polish. They love soccer and follow the Polish national team (currently ranked 5th in the world!) and stars such as Kuba Błaszczykowski and Robert Lewandowski. They want to establish Polish citizenship as well because in true ten year old fashion, they plan on both playing professional club soccer in Europe and believe they will have to choose between joining the national teams of Poland and the United States.