From the Warsaw Zoo to the American Dream

Vivian Reed

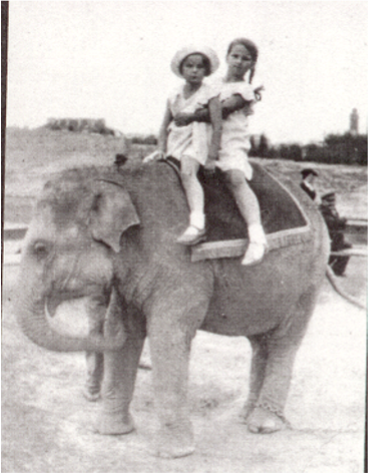

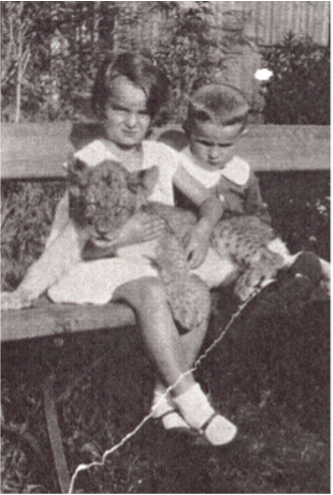

There is nothing sweeter than happy childhood memories. These photos, taken on a family trip to the Warsaw Zoo in 1938, show my mother (Stefanie, here age eight), her sister (Ricarda, age nine) and little brother (Georg, age four) remembered the day fondly. Stefi and Rickie enjoyed an elephant ride. Later, Stefi and Georg snuggled a baby leopard. The weather was warm and their joy was pure. Neither the children nor the young animals had any notion of the chaos into which their happy world would be thrown one year later.

Sixty years (in 1998) later my mother and I had occasion to look at these photos, tucked into a well-traveled but little seen album. As Mom’s seventieth birthday approached (in 2000), my four sons and their cousins had many questions about her background. Of course they were familiar with her lilting accent but were puzzled by the constant stream of World War II books she read. When the boys were little, the favorite game with Grandma was “hunt for Nazis.” As young men, they thought to ask why she loved to play that game with them. I was at a loss to answer – at least coherently.

Warsaw Zoo, summer 1938. Stefanie and Ricarda ride the baby elephant, Tzunika.

Stefi and her family rarely spoke about the part of her past that predated her wedding to my all-American father. So being a loving daughter and curious historian by then, I invited my mother for a long weekend at the lovely Columbia Gorge. Armed with a few old photo albums, including the one containing the photos above, and a bottle of wine, I invited her to talk. She was hesitant at first – for every question I asked, the answer was “complicated.” However, as so often happens with memories, once the dam was broken, a tidal wave began. The memories did not arrive in the neat chronological order my historian’s brain craved – memories are rarely to neat. Over the course of the next two years, Mom and I carved out 5 more weekends of focused time. We talked long and fast, often 18 hours a day, and rearranging hundreds of sticky notes became our modus operendi. In the end, we had a coherent story to share with the family. What a privilege!

At the time the photos above were taken in 1938, Stefi (Mom) was a Polish child like any other. Her father, Hugo, was a teacher and a Polish patriot who had fought for Polish independence in 1918 and defended Poland during the Polish-Soviet War through 1921. He endured two periods in Russian prison camps. In 1925, Hugo married Kasimira, a young Polish girl from a small town in the country. Their children attended local schools and the family was well integrated in their community. The only thing that set them apart from their peers was their Lutheran church

All that changed on September 1, 1939. Very shortly after the German invasion of Poland that began that fateful day, Stefi and her family became detested outsiders because of their last name – Scheiermann. Never before had she thought of herself as anything but Polish and could not understand why her friends now called her “schwabe.” She had no idea what that actually meant, only that it was said with hate. At nine years old, that was baffling blow!

It was only at that time that Stefi learned that her father’s family had emigrated from Germany to Poland several generations earlier. Her father, it turns out, was the first in his family to marry an ethnic Pole. Kasimira left the Catholic Church to marry Hugo and became Lutheran. In early 1940, Hugo made the gut-wrenching decision to apply for volksdeutsch status. Their lives were forever changed when it was granted.

Warsaw Zoo, summer 1938. Stefanie and Georg snuggle a baby leopard.

Yes, being volksdeutsch meant access to better and more food. Yes, it allowed Hugo a job in Warsaw, to travel with relative ease and provide better city housing for his family. However, it also meant some difficult things for Stefi and her siblings. Now that they were “German” and lived in Warsaw, they were “encouraged” (on pain of their father’s privileges) to attend the German school. Having never spoken a word of German, the children were required to attend classes all in German. They were punished if caught speaking Polish, even to each other on recess. The next development was difficult for my mother. She, and her siblings, were required to take part in the Hitler Jungend program at school. While Stefi did not mind the swimming and other exercise, she detested the marching and what she remembered as “mind programing.”

Simply trying to understand these difficult events proved consternating, with the limited information available to a child during the war. “Why?” was a constant question. “Why am I suddenly German if I am still Polish?” “Why do my friends hate me now?” “Why can’t we buy bread from the usual Jewish baker?” “Why did the previous tenants of our new apartment leave behind such beautiful things?” “Why do ‘they’ kill people in the streets, right in front of me?” Why indeed?

Another puzzle for Stefi was the strange behavior of her Polish grandmother. As the war developed, she seemed to know information the family did not and often left family dinners abruptly. As the family discovered much later, she was active in the Polish resistance. She served as a courier and in other unknown roles. When the Scheiermann’s fled Warsaw in July 1944, she remained to fight with her countrymen despite the family’s pleas to flee with them. She perished in the conflagration of Warsaw that began August 1, 1944.

As my mother talked, I came to understand her previous hesitation to speak of those war years. After being Polish in 1939, German in 1940, a refugee in 1944, a displaced person from 1946-1950 and an immigrant in 1951, Stefi embraced becoming a US citizen with her whole heart in 1957. Muddying her complicated feelings about her prior nationality was the new communist regime in Poland, which she abhorred. Not surprisingly, she found it all difficult to talk about – especially to her children and grandchildren. Most Americans, it seemed to her, equated Germans with Nazis and Poles with communism. Better to be an American, and leave it at that!

My mother and I presented a collection of her stories to the family at her 70th birthday party in 2000. But it wasn’t until The Zookeeper’s Wife by Diane Ackerman was published in 2007 that I realized the wider historical significance of that innocent elephant ride. The little elephant, Tuzinka, was famous from the day she was born at the Warsaw Zoo in 1937 - the only baby elephant born in Poland. She is now recognized around the world from her role in The Zookeeper’s Wife,(especially from the 2017 film version of the story). During the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, Tuzika was captured by Lutz Heck, director of the Berlin Zoological Gardens, and removed to Berlin. She died there in 1944.

As the years in American passed, the Scheiermanns passed, too, one by one. Sadly, Stefi herself passed away in January 2021. It seems an appropriate time to honor her story.