Patchwork School and the Desire to Learn

Mary Szostak-Sitko and Taylor Lenze

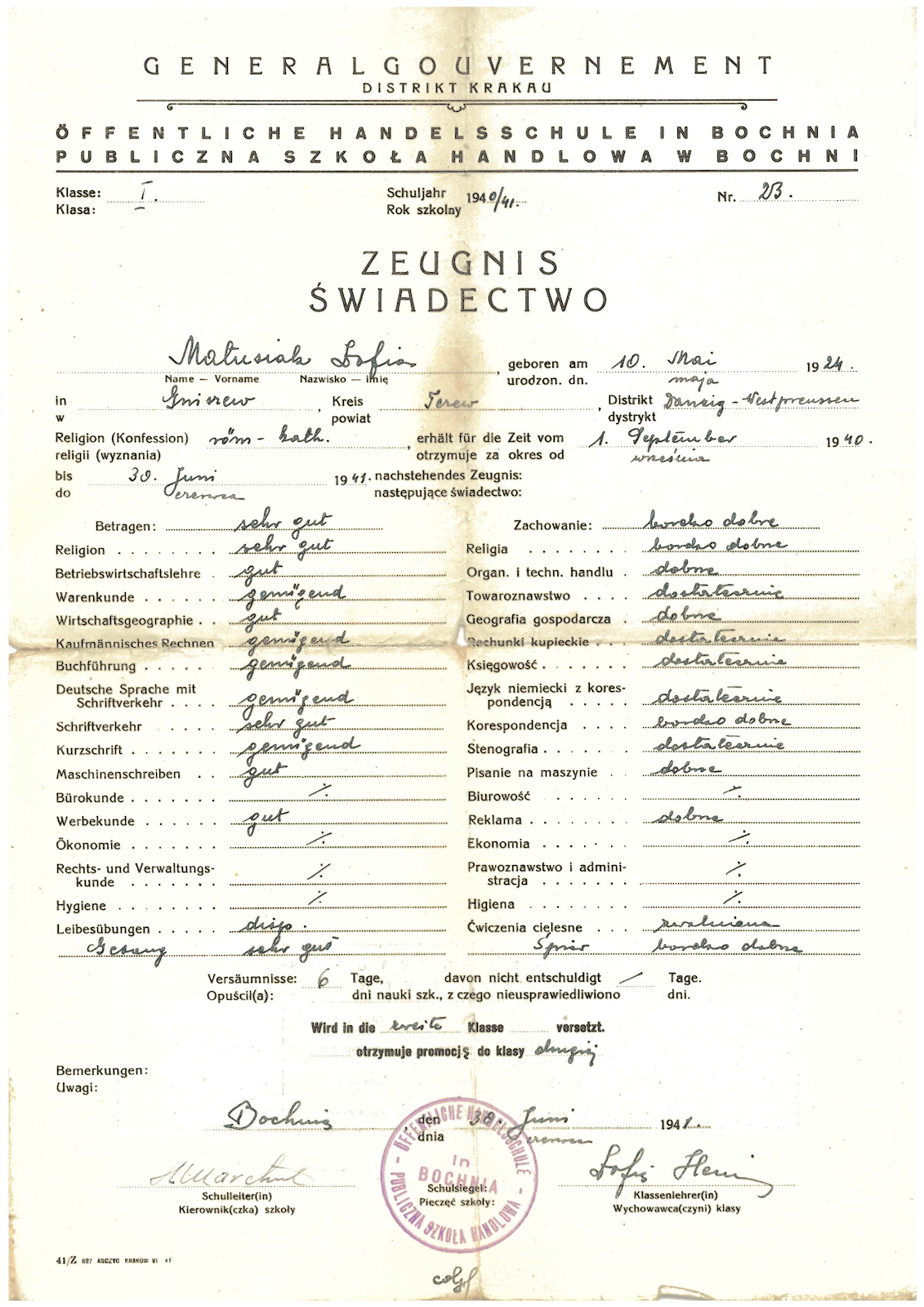

“Matusiak, Zofia:” so reads the hand written name on this German-Polish bilingual school certificate from 1940/1941. It shows Zofia having finished her first year at a public trade school in Bochnia with an overall grade of “very good.” Only missing six days of school the entire year, all of which were excused, Zofia seems to have been an excellent student, despite war and the Nazi occupation of Poland. Later, after escaping Poland and immigrating to the US, she would later go on to study at Wayne County Community College and Macomb Community College in the 1970s, preparing for nursing school and studying respiratory therapy, continuing until the illness of her husband in 1978.

Zofia’s educational path wasn’t an easy one though. Born to unwed parents, she lived temporarily in an orphanage before being officially adopted around her 5th birthday in 1931. Before the age of 10 she had already been in three different schools. At 10, she moved with her adopted family from Gdynia to Bochnia (near Krakow) where she attended Szkoła Leśna (Forest School), Św. Kinga School, and Clementine Tańska-Hoffman Gymnazjum.

In 1939, with “sounds of planes over head and bombs in the distance,” Poland was invaded and normal school suspended. She was just 15. Her daughter writes how “The war ended [Zofia’s] formal education. In 1940 the Germans opened a gymnazjum, Handelsschule Publiczna Szkoła Handlowa.” It was from this school that she received the certificate pictured above. Here the emphasis was on the German language. “During World War II the Germans only allowed students to complete two years of formal (high school) education,” both of which Zofia successfully completed.

After graduating, the German occupation of Poland didn’t allow her to get a job but rather she worked alongside Jewish girls from the Bochnia ghetto sewing buttons on Nazi uniforms along. Later Zofia made mattress covers in another German factory and mended underwear owned by wounded Nazi soldiers. Her pay was two pieces of bread, butter and soup a day. Zofia wrote later that “at least I had the satisfaction that our enemy also suffered during this time.”

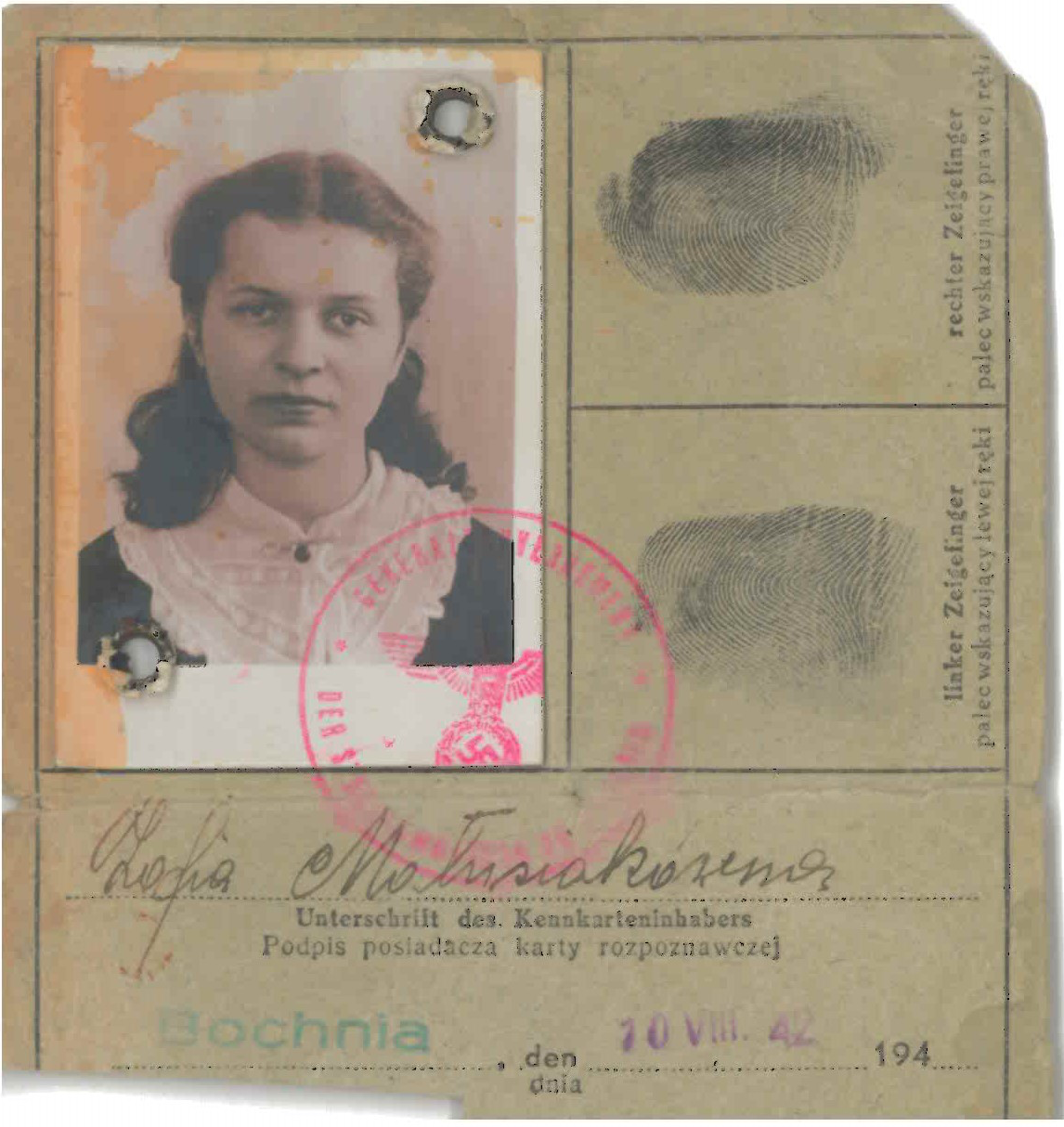

In 1942 however, Zofia’s two-year, Nazi-organized training at the trade school became her weapon to turn against them. At the age of 18, she joined NOWK, Narodowe Oddziały Wojskowe Kobiet [National Military Organization Party for Women, part of the Home Army. At the school, she had practiced typing and writing skills (Schriftverkehr, Kurzschrift, Maschinenschreiben) and now she could actively help the resistance as a “stenographer, sitting by the radio and typing messages that later would be printed for the people to learn what was happening during the war.” “This gave me a feeling of belonging somewhere and being able to do something worthwhile” she told her granddaughter Theresa.

Despite slave-like working conditions on German production lines, working in the resistance, and the lack of further formal schooling options, Zofia’s desire to learn wasn’t curbed. Instead, she enrolled at the secret “Flying University.” Her daughter explained how, “much of Zofia’s remaining high school education was done in secret during the war, moving from building to building in the town so they wouldn’t be caught. At that time there were many professors that were discovered, arrested and executed. Zofia received her Świadectwo’ (diploma) July 4, 1945. She also completed a teaching certificate, Kurs Pedagogiczny, on July 28, 1945. Since so many teachers and professors were killed by the Nazis, the intent [was] for her to start teaching after completing this five month course and then to continue preparing for full qualification as a teacher.”

She was an excellent writer and could write on any subject. Zofia remembered writing an essay in ‘The Era of Positivism and its Actuality in Our Time’ in the summer of 1945. “I saw the need for applying the ideas of the era at a time in rebuilding a new Poland,” Zofia told her daughter in 1999.

Upon receiving diploma from the gymnazjum, Director Galas “left his position and shook her hand and said “Your German (she had to write it in German) was terrible but I have to congratulate you on your Polish essay. It was great; you have talent. I am sure all of us will be proud of you.” Little did anyone know that she would leave Bochnia only a few months later on December 2, 1945. In reflecting those words Zofia said “No, I never became a famous writer, but whenever possible, I defended my country’s name.”

Primary Source: The Doll in the Rubble by Mary Sitko

Quotation Source: https://www.mimemorial.com/obituaries/persons/S/Zofia

Photo Source: Mary Sitko’s files