The Musical Heritage of my Polish - American Family

Victoria Ann Granacki

My Polish-immigrant grandfather played a curious-looking concertina accordion every evening in his third-floor flat. It had a floral pattern in the squeeze-box folds, an incomprehensible series of round silver buttons in the right hand, and just four base notes in the left. But could he make that instrument sing with polka-tunes! As a little girl I wandered upstairs to sit at his feet while that lively three-step dance beat its way forever into my soul. A few years later when I began piano lessons, player and audience were reversed. I practiced relentlessly on a tinny old castaway upright that my father had dragged into our basement. But no matter -- my grandfather sat in rapture, assuring me I played like Paderewski. Perhaps he heard the Polish rock-star pianist in 1939 in his last concert at Chicago's Auditorium Theater, overflowing with his fans. Of course, at that time I had no idea. I only knew my grandpa listened to me tirelessly and admiringly.

Joseph Granacki had immigrated from a small farm in Krasny Bor, in the Augustów region of Poland, arriving on the S. S. Rotterdam at Castle Garden, New York November 5, 1900 when he was just 23. He traveled alone but his passage was paid by his older brother, Stanley who had arranged to meet him in South Bethlehem Pennsylvania. Their family had been farmers, and their grandfather, Piotr, was a custodian of the Augustów Primeval Forest with its long history of tree-hive beekeeping. But like so many others, Joseph saw little future for himself there in the last decades of the Russian partition. Once in the US, his work-life was varied. He started at a tanning company in Coudersport, Pennsylvania where he met my grandmother, Victoria Fieczko, (after whom I’m named) and the pair married in 1902 at St. Augustine Church. She had made the journey at age 15 with others from her village near Suwałki and arrived in New York in April 1900. After returning from a disappointing trip back home to Poland where their oldest son died, the couple wound their way to the Midwest. Joseph built houses in Racine, toiled briefly as a machinist in Milwaukee, then farmed and tended bees in Door County. He and his sons (with my father) hauled stone for the foundation of Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Catholic Church in Pulaski Wisconsin. Finally, February 9, 1929, on the cusp of the stock market crash and Great Depression, they arrived by train in Chicago, where they settled in a Humboldt Park six-flat. All the way Joseph carried the music he passed to his children.

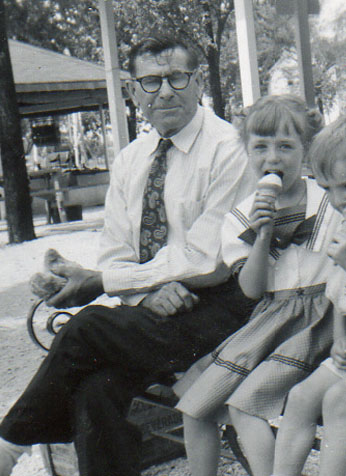

Joseph with granddaughter Victoria

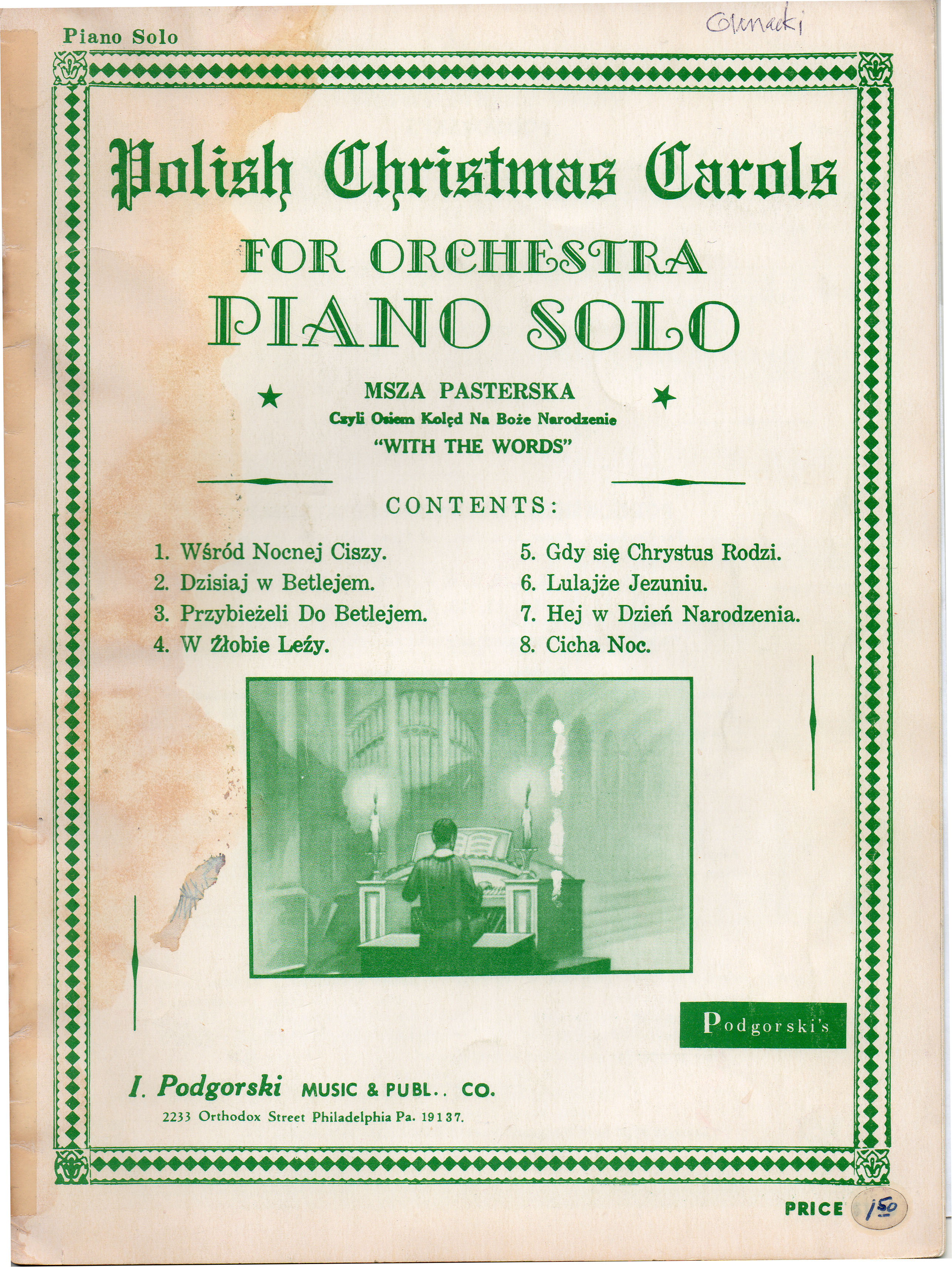

As Joseph and Victoria’s children grew and married, each couple crowded into that 6-flat which brimmed with extended family by the time I was born. The women were singers. Choir singers, soloists, accompanists. The church choir at St. Fidelis was their faith and their social scene wrapped together. And they brought song to every Christmas celebration. By the time my own parents had moved us to our 3-flat on a wide, tree-lined street in the Old Irving Park neighborhood of Chicago, it seemed like an estate. One year Christmas was at our house, the next, upstairs at my Aunt’s and Uncle’s. But each flat had a piano and after the last Wigilia plate was cleared and the men had begun the kitchen clean-up, the women launched the caroling. English songs at first, but then the Polish ones – Dzisiaj w Betlejem, Gdy się Chrystus Rodzi, and Auntie Joy’s special favorite, Lulajże Jezuniu. We had sopranos, we had altos, and soon the men wandered back in to provide the baritones. After my accompanist aunt could no longer play, I was an inadequate replacement, but I hoped if I loudly led the song, the piano errors would go unnoticed. Age eventually diminished the sound of the song but not the enthusiasm of the singers.

There were Polish weddings in our family every season. The traditional Catholic morning wedding mass had brimming bridal parties but afterwards families just scurried home to do afternoon chores. Guests came back at night in their finest suits and cocktail dresses for a copious banquet - always family-style - with Polish Sausage/sauerkraut the signature dish. And then as the local polka band soared, the dancers began to fly! Women predominated on the dance floor – moms and aunts and girl cousins -- and I bobbed with them all. But my father was the special dance partner I coveted more than any other. An excellent ballroom dancer who courted my mother in the mid-1940s at Chicago’s glamourous Aragon and Trianon ballrooms, he began my tutorials as soon as I was old enough to stay awake. Guiding me with firm hand and twirling me around so my dress billowed, we circled the dance floor endlessly until the chandeliers were spinning and faces a blur. Wedding after wedding we danced, with our last dance at my own wedding. He’s been gone for almost thirty years now but there’s still no one who can ever replace him as my polka partner.

Victoria with her father, Leon Granacki

The Globe “Gold Medal Accordeon” that was our family’s musical foundation is now mine. It’s been packed away in a yellowed cardboard box in my basement since my grandfather died in 1960. My hopeful attempts to play his favorite polka over the years have been feeble. But as a historian I’ve tried to understand a little about our family treasure. Globe was a German manufacturer, but this accordion was made for the American market in the early 1900s. It’s diatonic, which means from the same button, a different note sounds when you squeeze in compared to when you pull out. The double row of buttons is in the key of C and the four base levers play C, F, and G. Metal tags boast “improved steel-corner bellows” and its steel reeds are ‘warranted.’ The bellows seem brittle and even though I remember him refurbishing the reed sealing bars with suede lining and painting the tips red, that was over 50 years ago. Can I find someone to bring this ancient accordion back to working order? Is there someone to play it once again?

Music of all kinds has been woven into my life and is still with me, but perhaps not with my children or grandchildren. Something so precious and full of memories to me is probably a cumbersome relic to them. My grandfather’s Globe-tapping and my father’s dancing forever set the polka beat in my bones, and my aunts’ voices on their favorite Polish carols continue to haunt me every Christmas Eve. How can I care for this accordion artifact to bring the same musical joy to others?