WINGS OF MEMORY: A FAMILY’S LEGACY OF ART, WAR, AND POLISH IDENTITY

by Anna Muller and Iwona Flis

Anna met Bex in the summer of 2019 in Rwanda during a memorable dinner. For Anna's group, it was a final meal marking the end of a week-long workshop on resilience and trauma; for her, it was a farewell dinner with a group of women celebrating the conclusion of their time in Rwanda. The restaurant was cozy and intimate, and the food was delicious. Both groups were seated close to one another, and at some point, they found ourselves chatting. Anna does not even recall how they began discussing the Polish American Historical Association, but the topic somehow came up. Over four years and one pandemic later, Anna and Bex started exchanging messages about an object—a painting that had hung in Bex's parents' house for decades and came into her possession a year ago.

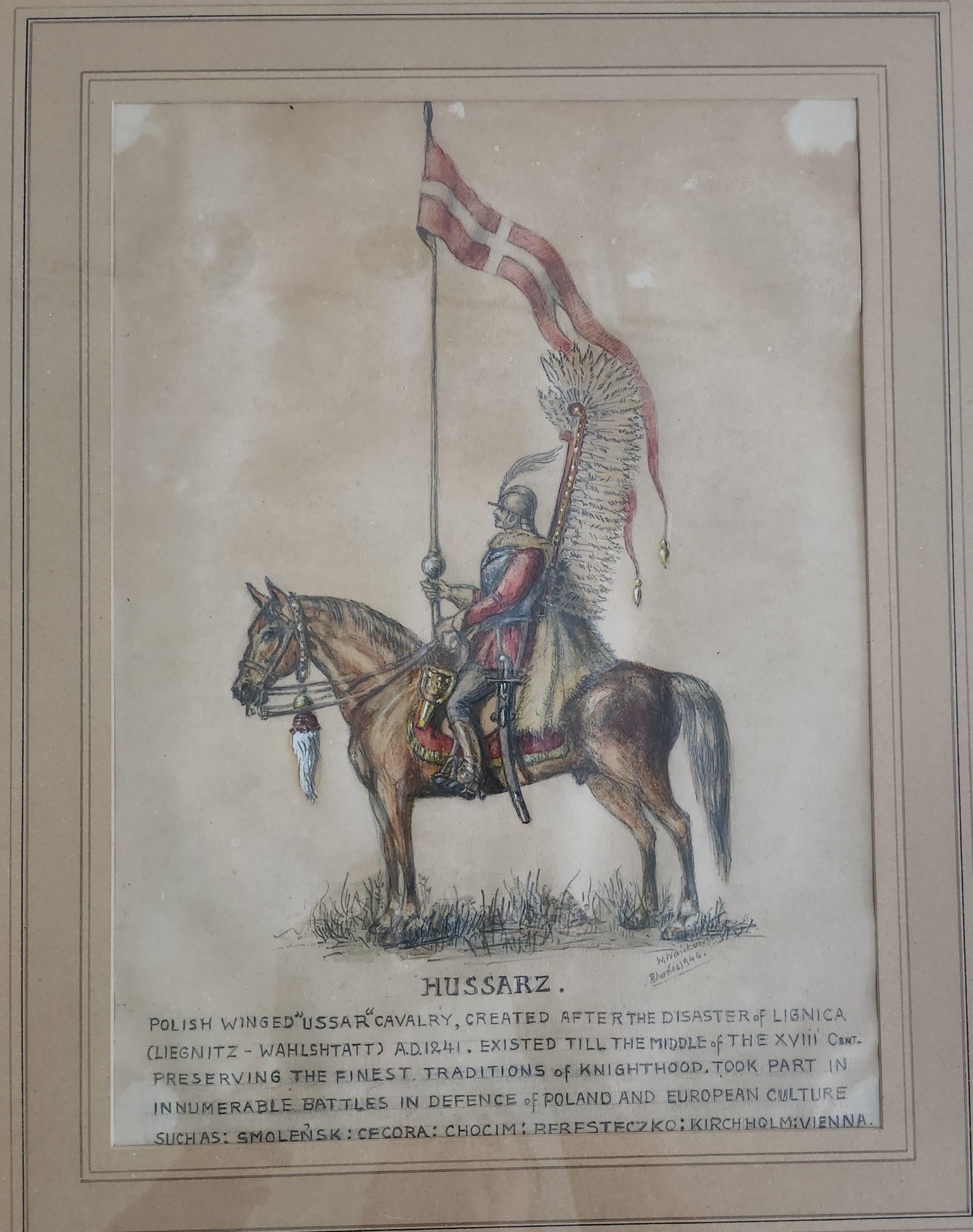

A drawing of a man on a horse had long adorned the house where she lived with her parents. The image depicted a Hussar, a soldier of the Polish cavalry, with his distinctive wings attached to the armor. It was rendered in colored pencil with meticulous attention to detail. At the bottom, there is an inscription that reads: “HUSSAR cavalry, created after the disaster of Legnica, AD 1241. Existed till the middle of the XVIII century, preserving the finest traditions of knighthood, took part in innumerable battles in defense of Poland and European culture such as Smoleńsk, Cecora, Chocim, Peresteczo, Kircholm, Vienna.” The drawing is dated 1946 and bears the name W. Wańkowicz, with Rhodes listed as the location where the painting was done. It was an image that captivated a child. Years later, Bex realized that the artist behind the image she had admired since childhood was her grandfather.

Bex knew her grandfather, Witold Wańkowicz, through the stories her father shared and the various beautiful memorabilia he left behind—each piece a testament to who he was. Among these items were an old, tattered UNRRA flag and his self-published, leather-bound memoirs, in which he wrote about his work for the Polish government during the war. "He was fiercely Polish," Bex recalls.

Witold Klemens Wańkowicz was born in 1888 into a noble family in Poland. In 1915, he married Jolanta Römer, a member of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility. With the rebirth of an independent Poland in 1918, he began his diplomatic career. In 1919-1920, he served as the deputy general delegate of the Ministry of Provisions and as deputy delegate of the Polish government in Gdańsk, where he coordinated shipments of American food aid to Poland. In the 1930s, he held the position of chargé d'affaires and Counselor at the Polish embassy in the United States. Among his many contributions, he played a key role in organizing the Polish pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair in New York.

Witold Wańkowicz with women in traditional Polish dress at the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair. Source: Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Poland Participation - Witold Wankowicz with women in traditional dress" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 15, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e9-13a4-d471-e040-e00a180654d7.

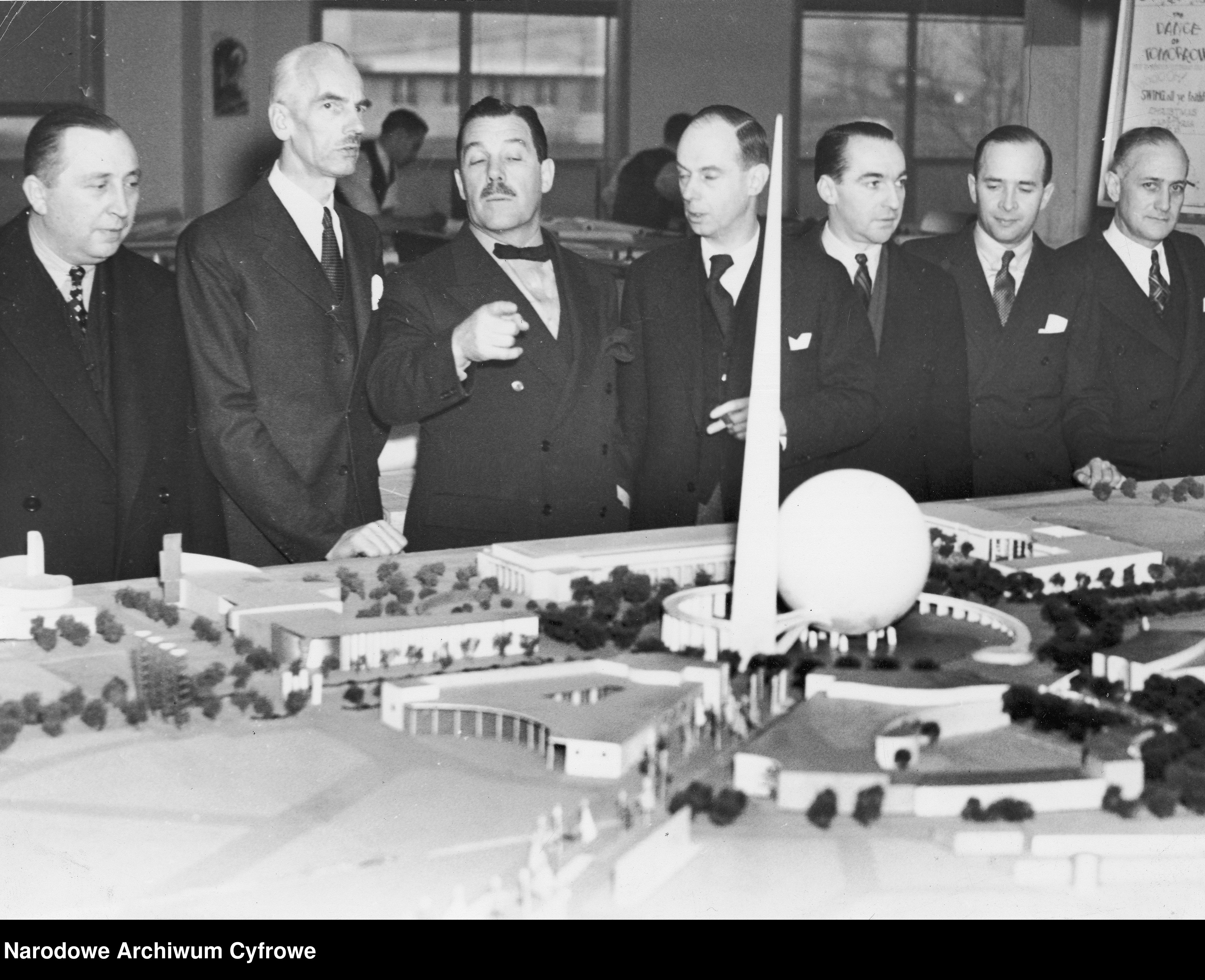

In another photo from that period, we see Witold Wańkowicz with a group of Polish diplomats, studying a diorama of the exhibition halls. Shortly thereafter, the Second World War began, and he and his family never returned to Poland.

The date on the Polish Hussar drawing is accompanied by the name of a place: Rhodes. In 1945, Wańkowicz was appointed as a representative of the UNRRA to one of its 16 missions, specifically to the Dodecanese Islands, then under British Military Administration (BMA). He continued his humanitarian work there, which he had begun during World War I with the Red Cross and later continued in Gdańsk. In November 1945, he joined the BMA’s Central Relief Committee. As the Deputy Chief Welfare Officer of the UNRRA Dodecanese office in Rhodes, Wańkowicz personally addressed repatriation and relief efforts, demonstrating compassion and understanding toward those in need. In his correspondence with other UNRRA officials, he expressed concern about the future of relief work following the UNRRA mission's conclusion in December 1946 and the transfer of the Dodecanese Islands to Greece in 1947, anticipating further food shortages. He continued his humanitarian efforts in the region, eventually becoming the chairman of the Dodecanese Welfare Association, which took over the remaining UNRRA resources.

Separated from his own country and deeply involved in facilitating repatriation, as well as providing food, shelter, and other basic necessities to refugees of various nationalities, Witold Wańkowicz still found time during his mission in Rhodes to draw the Hussar depicted here. Was this simply an exercise in drawing, or was it an expression of his longing for Poland’s great past and hopes for a brighter future? Based on what we know about Bex’s grandfather, we believe it was the latter. He had, however, a life-long interest in drawing and painting, and often the two (expression of longing for Poland and drawing) overlapped. The family has preserved many of his sketches and paintings that illustrate this.

The Polish Hussar drawing, created by Wańkowicz in Rhodes and later cherished as a precious memory in the U.S., can be seen as a symbolic reflection of his family’s fate. Witold Wańkowicz lived nearly half his life exiled from his homelands. The family estates were looted in the Bolshevik revolution and later ceded to Belarus by the Treaty of Riga in 1921. Because of this Wańkowicz was never again able to go back there. After World War II the situation worsened. Unable to return to Poland due to its grim postwar reality under communist rule, the family became dispersed across continents, yet held fast to their Polish roots and treasured their memorabilia. Witold Wańkowicz’s daughter, Jolanta, and her husband, diplomat Gilles de Boisgelin de Pléhédel, became patrons of the Polish painter Józef Czapski and helped establish one of the finest collections of his work. The youngest sibling, Paul, Bex’s father, who kept the Hussar drawing in his home, trained during the war to fight with the Polish squadron of the RAF. He also had a dual commission in the Polish Air Force. After the war, he became a highly accomplished engineer and, like his father Witold, engaged in humanitarian work, serving as a representative of the U.S. Agency for International Development in An Xuyen province, Vietnam, for two years. It wasn’t until his 60s that he reconnected with his heritage by joining a group of Polish veterans of foreign wars. He began speaking Polish again and eventually felt the need to return to his homeland. After many years in America, he finally made the journey back, taking his daughter with him to show her Poland through his own eyes.

Since the death of her father last year, Bex and her siblings have been slowly sorting through the memorabilia, photographs, and documents their grandparents and parents left behind. These items hold vast knowledge, deep emotions, and a key to understanding the experiences of Bex’s grandparents, Polish nobles who arrived in the United States with hopes of working for Poland, likely never expecting they might not be able to return. Though they made the United States their home, their ties to Poland never faded. As part of preserving their legacy, the family is reorganizing Witold Wańkowicz’s documents and preparing to donate them to the Polish Museum in Chicago. This careful reorganization ensures that these valuable records will be properly archived and accessible to future generations. The hope is that through this effort, more people will come to understand Wańkowicz’s significant contributions to Polish history, preserving the finest traditions, as the Hussars once did.

Jolanta and Witold Klemens Wańkowicz with their daughter, Irene Wańkowicz (Chościak-Popiel).