Being Polish American

Mark Dillon

"We always knew you would come back": A conversation with Mark Dillon.

By Anna Miller and Marta Cieślak

Can you tell us who you are in the way that you would like to introduce yourself to the members of the Polish American Historical Association?

A native New Yorker, I grew up in suburban New Jersey in a second generation Polish-American household in the 1970s in Sayreville. Once an industrial, largely Polish immigrant town named for a brickmaker, it is perhaps best known as the boyhood home of Slovak-American singer Bon Jovi.

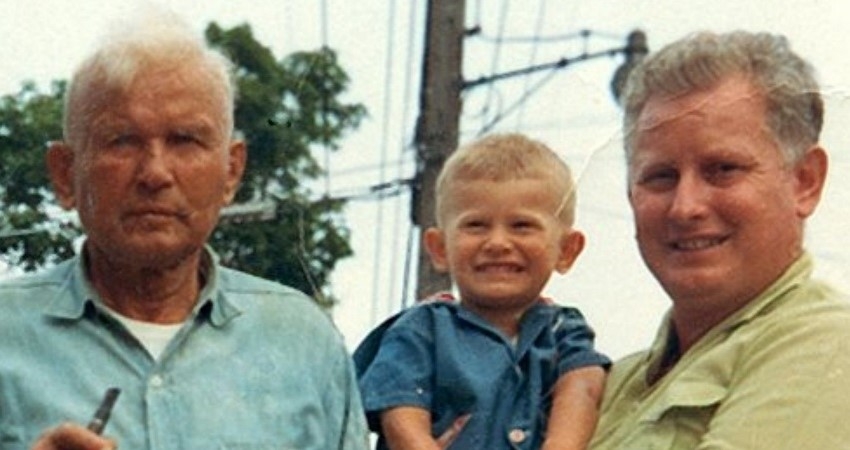

For the past 21 years, Minnetonka, Minnesota has been my home with my Polish-Irish heritage wife Cecelia (here’s us posing at left near Wawel Cathedral in Krakow in 2018). Our Upper Plains venue was the byproduct of my two-decade long career path in financial services communications for global asset managers that included the company formerly known as American Express Financial Advisors, now Ameriprise, which relocated us from Evanston, IL north of Chicago. We came for jobs, and have stayed for the natural environment.

Can you tell us a little about your familial background? Where did you grow up? And what stirred your interest in Polish and Polish American history?

My exposure to Polish-American culture began at an early age, having attended Sacred Heart School in South Amboy, NJ, a now closed K-8 Roman Catholic parochial school where many of my classmates were of 2nd and 3rd generation Polish heritage, and one year of a Saturday Polish language and culture class in grade school.

More influential was being blessed with an extended U.S family where our ancestral roots were appreciated. My fraternal grandfather, Maciej Dylag, emigrated from the village of Libusza in the Carpathian foothills and Americanized his surname of Dylag to Dillon when he arrived in July 1905 on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II and settled in Newburgh, NY. Maciej would wait until age 43 to wed Theresa Pavlovic, daughter of 1st generation Slovak-Americans Michal Pavlovic and Carolina Macejka from Kuty 40 miles north of Bratislava. February 2024 marks Maciej’s and Theresa’s 100th wedding anniversary.

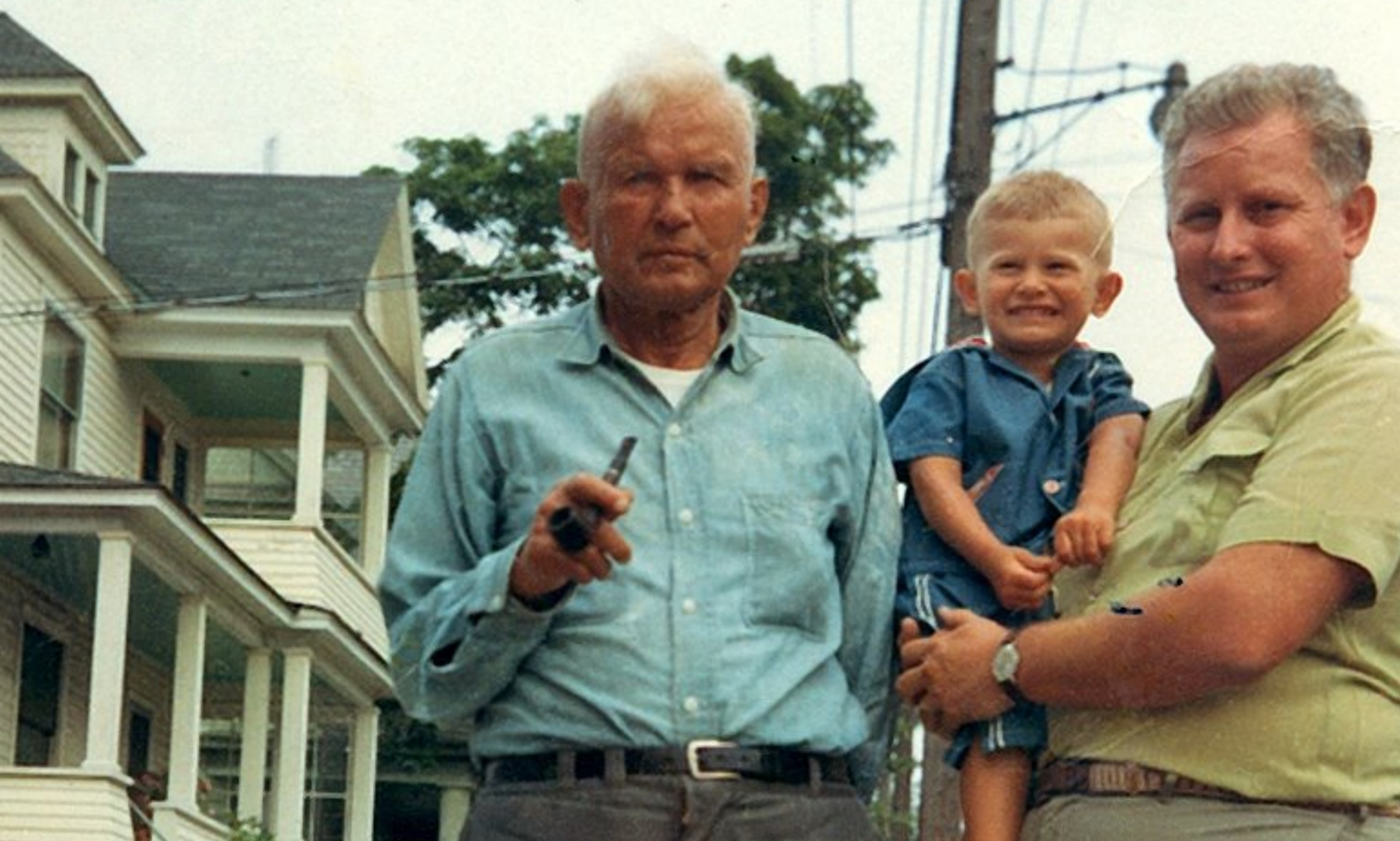

Maciej Dylag, Mark Dillon and Francis J. Dillon in the summer of 1966 in Amsterdam, NY. The photo is taken from Bryk’s Corner Market, a family owned Polish deli and grocery store owned by Mark’s Uncle Mack.

Maciej and Theresa would have three children before a negative reaction to anesthesia during a tonsillectomy cost Theresa her life in 1935, leaving Maciej a single dad. My Dad, then age 10, would stay with Maciej while his younger brother John and sister Mary moved to Amsterdam to be raised by relatives. John would become a turbine engineer at GE while Mary a registered nurse who married Mack Bryk, a grocer and Polish deli owner whose kielbasa recipe became a city-wide favorite.

My maternal “all-Polish” side provided childhood exposure to Polish American culture as expressed in the cuisine, Roman Catholic faith expressions and the urban immigrant experience of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg neighborhoods of Brooklyn, NY. Rozalia Stepien Prus left her husband Jakub and six children in Dzikowiec, Poland near Kolbuszowa in 1911 to emigrate alone on the SS Rhein. One of her daughters, Weronika, my grandmother, came two years later at age 16 in March 1913 with a relative, joining her on South 2nd St.

Weronika’s daughter, Helen, my Mom’s sister, would become the steward of Polish holiday traditions, with many a childhood Christmas and Easter gathering at her 8-unit brownstone on North 7th street that our family would own for 80 years, purchased by Helen’s husband’s father one month before rent control went into effect in New York City in 1940. My parents would marry in 1959 at nearby Our Lady of Consolation Church, a Polish congregation.

As rooted in Polish-American culture as my family was, only the most rudimentary language skills were passed on, with no real family contact overseas. My father had built his life and career on English – as the Class of 1939 valedictorian at St. Francis in Newburgh, as an award-winning playwright in college and an advertising manager for New York agency Young & Rubicam and others. My path was similar, as a journalist at The Asbury Park Press, and a communications leader for asset managers in the days when annual reports to shareholders and commentary were more than emasculated boilerplate.

This all changed in May 2014 with my first of five visits to Poland when it became as clear as the air on a spring Adirondack morning why Maciej had picked upstate New York to begin a new life – in these green hills were the new Carpathians. Two years later, I was also able to discover my Slovak heritage that had been all but lost since 1935.

After remarking that I was the first Dylag family member from America to return to Poland in more than 100 years, one senior cousin joked while we were in the Libusza cemetery, full of headstones with familiar surnames, that “We always knew you would come back.”

It sounds like you have put quite a lot of time and effort into getting to know your ancestors’ lives and stories? What prompted you to engage in genealogical research? And would you have any tips for our readers who are thinking about it but may not be sure where to start?

My four grandparents died before I got a chance to know any of them, and both my parents died at a young age, 57 for my mom and 60 for my dad, when I was in my 20s. I was 9 when my fraternal grandfather passed away. This all prematurely shortened my ability to learn my family history., A cousin, William Novak, had traced parts of the family tree in the 1980s that I built upon with in 1993 additional U.S. records after two uncles whom I was close to died. However, It really wasn’t until 2013 when I turned 50, amid the expanded search opportunities of the Internet and partial digitalization of records in Poland and Slovakia, that my research efforts began in earnest. I had the time as my financial services career was winding down.

To start on one‘s geneaological journey, I would say access not only marriage, death and baptismal records. Do as much background reading, viewing of webinars and videos from informed sources as you can about the time and places where one’s ancestors lived. This helps set the context to appreciate the life choices one’s ancestors made, and may provide guidance as perennial human issues resurface or take on new 21st century forms. Take more than one DNA test and take a trip to one’s ancestral homeland as early as you can, and include sites in addition to the tourist spots.

When you discover your extended family in Poland, may I suggest using technology to connect the youngest generations with each other “across the pond’– maybe create a virtual play group so children can teach other words and share what they learn in school at their own pace. Let them build cross-cultural friendships.

My Polish journey was made easier and more fruitful through the Polish American Foundation of Connecticut’s Welcome Home program, which combines personal family research and tourism that made my first trip to Poland in 2014 more meaningful. My Slovak journey in 2016 was harder since there had been virtually no family contact since 1935. The Czechoslovak Genealogical Society International, whose board I now chair, was and is a great resource, notably for those looking to research families in Silesia, the Tatras and the cross-border areas of the Carpathian foothills. (www.cgsi.org)

What did the trips to Eastern Europe help you understand about yourself and your family?

To my joy and delight, in both Poland and Slovakia, my extended families are growing and thriving, especially in a family sense. Technology allows us to bridge time and distance, to build and maintain connections, and this I believe is a key element of both preserving and redefining Polish American culture, and cultural groups. For example, a few years ago I facilitated a mobile phone conversation between my father’s brother, then in his 80s and his first cousin, in his 90s, whom he had never met. The GE engineer’s childhood knowledge of Polish came back to him. It is moments like hearing and seeing my preschool age Polish niece read the story of the Three Little Pigs in English live from a Krakow suburb via video that brings together our global Polish family.

Over the past decade, I became more involved in the institutional aspects of Polish American culture, initially through Minnesota groups but also reaching out to groups in Connecticut, where my maternal grandmother’s Weronika’s shipmate Jan Prus once operated a Polish grocery, to northern New Jersey to Chicago and upstate New York.

This has added and deepened my understanding of a very diverse, continually changing Polish American experience. Applying my journalism skills as a monthly columnist for the Polish American Journal has allowed me to see the fabric of Polonia, from a vibrant Kashubian community In Winona to Little Falls to the bigos that is Polonia in the Twin Cities.

Mark and Cecelia Dillon marking the 100th anniversary of Poland’s renewed independence at a Minneapolis Institute of Art celebratory event in November 2018.

Do you self-define as Polish American? What does Polish American mean to you? Do you think Polish American identity as a concept has changed over time or perhaps is changing?

I see Polish-American identity as having three components – family, communal and institutional. I believe that to the extent one can personally reach out to understand one’s extended family history and how Poles currently view Polishness rather than let stereotypes or political elites craft the dialogue, we come closer to seeing that all generations share much in common.

Sadly, I have learned over the past few years that in some venues in Minnesota and places like Washington, DC not all things labeled Polish are good. What appears sweet-sounding, authentic and inclusive on the surface can be a paczki filled with cyanide.

The noble Polish personality traits of shared traditions and fidelity to what our ancestors sacrificed and achieved also has an institutional dark side: extreme stubbornness, country-of-birth chauvinism, lack of governance transparency and a hoarding of power. Admitting to and addressing this duality can help Polish-Americans save struggling U.S. cultural groups that face declining membership.

Perhaps the historical American values of cross-cultural outreach, honest debate and tolerance of dissent can serve to curb Dmowski-style prejudice. Poles and Poles Americans can avoid repeating the self-inflicted mistakes of history that contributed to geographic partitioning, and thus begin to craft a shared, mutually respected global Polish identity. It is no easy task amid the challenges of a U.S. civic life where polarization and leadership misdeeds are part of daily news feeds.

I take inspiration from the Polish example of kindness and civility set by my aunt Helen, as well as the courage and perseverance of her husband Chester. I think his military experience of driving an Army truck and dodging snipers on Okinawa in 1945 helped him survive as an urban homeowner in New York City’s in the late 1960s and 1970s. Both would live to see the renewal of their neighborhood in the 1980s and 1990s from a fresh wave of Polish immigrants.

It is an honor to learn from and participate in the gatherings of groups such as the Polish American Historical Association, Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences and Polish American Engineers Association, and others. It is also a blessing since February 2023 to see how much we have in common with our Ukrainian cousins, and how that transcends language and faith.