Being Polish American...

An American Student in Poland

and a Polish Family in America

As young children, my brother Stefan and I believed that having been born and raised in the distinctly multi-national environment that characterized New York City in the 1940s and 1950s, was not unusual. Our parents spoke another language (in this case, Polish) between themselves and spoke to their children in English. As we grew a little older, subtle differences between our family and others became apparent. Some were related to the fact that our father was paralyzed, our mother was a full-time professional who supported the family, and thus we were required to share the responsibility of caring for our father’s physical needs during the day and spend most of our time at home. However, of greater significance for me were the impressions left by the almost constant background of classical music played on the living room radio, the occasional comings and goings of older, distinguished looking people who spoke Polish with my parents, and the strictly traditional way of observing not only Christmas (with its obligatory “wigilia” celebration), and Easter (with my mother’s traditional cooking and her painted eggs), but also December 6th – St. Nicolas day (with its ginger bread “Santa Claus”). Just as important, perhaps, were the fragmentary tales of our family in Poland, as told to us by our parents. Finally, while we were never taught to speak Polish, the oft repeated request that we try remember to use common words of Polish courtesy (proszę, dziękuję, dzień dobry, do widzenia, dobranoc, etc.) when appropriate, may have solidified all of the above experiences, and instilled in us a certain pride in our family’s Polish heritage.

Later, following my father’s death, travels to Kraków and meetings with Polish relatives moved me to investigate further our Polish background and learn for myself about these family members and how each of them each contributed to the Polish culture which was so important to my parents. Still later, after the death of my mother, I read some of her more private papers that I had never known existed. I then understood even more fully how intimately her love for my father was tied to her love of her once adopted, and then lost, Polish homeland. I also learned that the cultural environment that I and my brother had experienced as children was not, as I had believed, solely a result of my father’s musical abilities, interests, and achievements. I learned that significant as these had been, they were matched, and perhaps even exceeded, by my mother’s poetic and literary talents. Thereafter, my search to understand the depth and breadth of my “Polishness” intensified. It resulted in my first feeble attempts to learn something of Polish language and literature, the publication of a small volume of my mother’s previously unknown poetry, and now the writing of our unusual family story.

It is the story of a chance meeting in 1931 of an American graduate student at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, the daughter of modest parents from a small town in America, and a Polish university student, son of a famous musicologist and university professor, during a class they happened to share. The several years that followed culminated in their marriage and brief life together in Poland. Following the sudden outbreak of World War II came their unwelcomed permanent residency in the United States. I believe that the story is both unique and historically interesting. Perhaps, and more importantly, it is the story of how each solely, and together, contributed to their beloved Poland and its culture, while also suggesting that while that which they were able to accomplish in this regard is interesting, valuable, and worthy of notice, that which they might have later accomplished would have been greater still were it not for the dramatic events that changed the course of their lives.

While not the primary purpose of this brief monograph, its writing also offered me the opportunity to superficially describe the contributions of other members of the Reiss family. The life-time contributions of my grandfather, Józef Władysław Reiss, are well known and documented in the history of Polish music, however the efforts of my cousin, Krystyna Witkowska-Reiss, to preserve Poland’s artistic treasures are also important and they deserve to be so recognized.

Finally, the process of writing this piece for the PAHA blog permitted me to further explore the common thread that bound these family members together, namely – their love for their Polish identity and their possession of both the talent and drive that enabled them to contribute meaningfully to Poland and its culture. In doing so, I also experienced regret that I did not try to learn more of my own heritage when my parents were still living and could have taught me, had only I asked.

Note: The appendices referenced in this piece, are available on request. The author would be pleased to respond to questions and requests. He can be reached at rfr1@cumc.columbia.edu

An American Student in Krakow: Elizabeth Munk Clark and her family.

Elizabeth Munk Clark was born on April 16, 1908, in Watertown, New York, to a rather modest but typical middle-class family of the time. Her father was Francis (Frank) Michael Clark, a young man born of second generation Irish and German immigrants, and her mother was Susan May Munk, daughter of parents with American roots dating back to the late 17th century. Aside from his occupation as proprietor of the grocery he co-owned with a business associate, Frank’s main extrafamilial interest was his active involvement in the activities of the local church. Frank and Susan had a second daughter, Mary Louella, born on November 23, 1912. Elizabeth and her sister were happily raised in this traditional and conservative family environment. Mary, who developed an interest in music and possessed a superior singing voice, graduated from the famed Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey. She was to later to return to the College, as its choir director, following which she directed the choirs of many important protestant churches throughout the United States. Elizabeth, on the other hand, had early on developed an interest in literary and classical studies. Also of note, she much later recalled that as she grew out of childhood, she developed a rather independent spirit that created considerable anxiety for her parents. That notwithstanding, Elizabeth always remained very attached to her mother and Susan’s death on November 25, 1936, affected her deeply. Following her death, Frank remained in Watertown tending his store and living in the family home, where he welcomed his grandsons to spend their summer vacations until his death on January 31, 1950.

.jpg)

aaa.jpg)

Elizabeth and Mary Clark, c. 1915.

At the early age of 17, Elizabeth graduated from the local high school and was admitted to Syracuse University to study English literature, with minor concentrations in French and German. She completed her studies for her Bachelor of Arts degree in only three years graduating cum laude in 1928 and subsequently left for the University of Wisconsin to pursue her Master of Arts in English Literature. After obtaining her degree in 1929, she remained at the University, undertaking studies for a PhD in comparative literature. During this time, she became fascinated with Slavic languages, and was referred to the head of the Slavic Language department, the noted scholar of Polish literature, Professor George Rapall Noyes, to discuss her interest. He easily convinced her to learn Polish as preparation for the study of its literature. Shortly thereafter, in 1930, Professor Noyes left to become the Chair of Slavic Languages at the University of California at Berkeley. Having learned of the possibility to spend one or two years in Poland with a fellowship from the Kosciuszko Foundation, and its requirement for an understanding of Polish, she followed Professor Noyes to Berkeley to study Polish language and literature with him during the academic year 1930-31.

Elizabeth Munk Clark, 1931.

Her relationship with Professor Noyes was to continue until his death in 1952, and thereafter for several years with his widow. The year spent with him was extremely fruitful. Not only did she learn the rudiments of the Polish language, but was able to publish, with him, a translation of Stanisław Wyspiański’s play "Protesilaus and Laodamia."1 It was at that time, she decided to write her thesis on the poetry of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Adam Mickiewicz, and to undertake the required research while in Poland.

She arrived in Kraków in the autumn of 1931 and enrolled as a visiting graduate student at the Jagellonian University. Shortly after arriving, she met her future husband in one of her classes. Her recollection of this event is appended in sonnet form. (Appendix 1). Her fluency in the Polish language developed quickly and she rapidly integrated herself into the student and cultural life of Kraków. Many of her student acquaintances in Kraków, were to become lifelong friends. Among them was, Ludwik Krzyżanowski, the future Cultural Attaché of the Polish government to the United Stated and Columbia University Professor, who is pictured below with Elizabeth. Another of her to-be life-time friends was a young British student, Mary Corbridge-Patkaniowska, also seen in the photograph, and, who, in addition to many other accomplishments, would later author the widely popular manual, “Teach Yourself Polish” and translate Oskar Halecki’s “History of Poland” into English.

.jpg)

The English Club, Jagiellonian University, c.1932. Professor Roman Dyboski, the founder of the English Studies department, in the center. Elizabeth Munk Clark in the first row to his far left. Ludwik Krzyżanowski, is in the second row directly behind her. Immediately to the right of Professor Dyboski is Mary Corbridge-Patkanowski.

For several weeks in the late summer of 1932, she was in residence at the home of the actor and dramatist, Mariusz Maszynski, in the small eastern village of Medyka.

During her stay, she translated a three-act play of his, subsequently staged in Warsaw in 1933, "Tak, a nie inaczej," (Yes, and not otherwise).2 At that time, she also translated another of his plays, that to my knowledge was never staged, "Medyka".

.jpg)

Elizabeth Munk Clark in residence in Medyka home of Mariusz Maszynski, 1932.

Her support from the Kosciuszko Foundation expired in 1933, but rather than returning to the United States to complete her PhD at the University of Wisconsin, she decided to continue her studies in Kraków, as a regular doctoral candidate. Her dissertation on Emerson and Mickiewicz was never to be finalized, however her detailed notes relating to this study, as well as some of her relevant personal communications, now rest with Professor Noyes’ papers in the University of California, Berkeley library. Some of her thoughts on Emerson were, however, published in Poland.3 In communications with her parents, she had only hinted that she had begun considering the possibility of taking up permanent residence in Poland. They only learned of her decision upon reading a 1936 issue of the Chicago based English language Polish American periodical, The New American. It had published an article entitled "An American Coed Makes Poland her Home," following an interview she had given during a brief return to the United States on occasion of her mother’s illness.4 In that unfortunate article, she was quoted as saying “the opportunities offered me in the United States, I can always find in Poland, and as to those unique to this country – they are of too minor consequence to be desired by me.”

During the years that followed, and while continuing her studies, she supported herself by giving private English lessons, hosting a talk show on a local Polish radio network, translating for the Polish Academy of Sciences, and even writing articles for the New York newspaper, Nowy Swiat (New World).

Following a romance that began during her first days of classes in 1931, she married Ernest Paul Reiss on May 5, 1937. Thereafter, she moved to Katowice to join her husband, and took a position as Confidential Secretary to the British Vice Consul, never again to take up her life in Kraków.

The Polish Student in Kraków - Ernest Paul Reiss and his family.

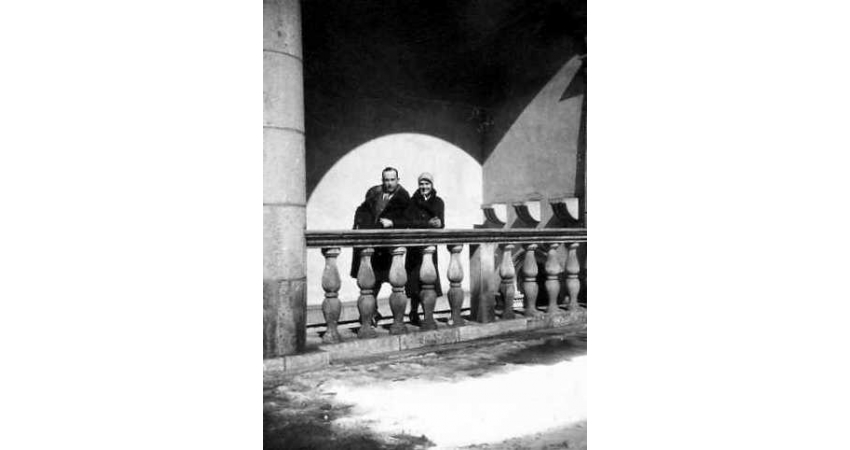

Ernest and Elizabeth Reiss c. 1937.

Ernest Paul Reiss was born on March 1, 1904 in Złoczów, a small city in Eastern Galicia (now Ukraine) into a family with Galician roots that I have been able to trace back to the period following the third partition of Poland in 1795. His grandfather, Elias Reiss, who apparently later used Emil as his given name, was born in Tarnopol, graduated in medicine from the University of Lemberg (Lwów) in 1874, and then, is reported to have served as a high - ranking surgeon in the army of Emperor Franz Józef.5 He married Barbara Damarska, following which, two children, Rosa Reiss and, notably, Ernest’s father, Józef Władysław Reiss, were born to the couple.

Dr. Emil Reiss with grandson, Ernest, 1915, Kraków.

Józef was born in Dębica, a large town in Galicia, on August 4, 1879. He began his university studies as a medical student at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow in 1898. Shortly after enrolling in the University, he left the faculty of medicine to pursue a degree in history. following which he studied musicology at the University of Vienna with the pioneer musicologist, Guido Adler. Upon his return to Kraków, he lectured at the Conservatory in Krakow while starting to write his PhD thesis “Psalm Melodies by Mikołaj Gomółka”, a critical review of this Polish renaissance composer, that was eventually published in 1911. After becoming established in his position at the Conservatory, he married Stefania Szymańczewska. Following the birth of Ernest, Józef and Stefania would have three more children; Tadeusz, Ryszard, and Maria.

Józef Władysław Reiss, c. 1908.

In 1922, he qualified for the “habilitation” certification with the publication of a study of 16th century polyphonic hymns, following which he joined the faculty of Jagiellonian University, where he taught until 1939 when the University was closed after the outbreak of world war II.

His prolific research and writing career as a music historian, encyclopedist, and musicologist began shortly after assuming his position with the Kraków Conservatory and following the above-mentioned publication of his doctoral thesis. Of the first of his 84 major publications that dealt with strictly musicological issues were Problem treście w muzyce (The problem of content in music), published in 1915, and Formy muzyczne (Musical Forms), published in 1917. His interests varied widely from Renaissance music to Silesian folk songs, as can be gleaned from an examination of his publications. Many of his early works also dealt with the history of Polish music, and biographies, including a critical biography of Beethoven, and another of the violinist and composer Henryk Wieniawski. (He was to write a follow-up study of Wieniawski in the post-war years, that was published after his death).

He was a recognized authority on the music of Chopin. In the late 1920s, he participated in several University Public Lectures, presenting talks on Chopin both in Kraków and other regional cities. It was recently extensively researched and reported that these lectures, as well as others regarding the beauty and importance of Polish music, were heavily attended and had a profound influence on the general public.6

Similarly, a series of adult educational articles on Chopin, "Koryfeusze muzyki polskiej". "Fryderyk Chopin" (The leader of Polish music. Frederic Chopin), published in the Silesian periodical Polska Zachodnia (Western Poland), were also very popular.7 Given that he was also very familiar with the traditional “klezmer” music of Polish Jews, it is interesting that he noted in his writings that to the amazement of many at the time, Chopin gained the reputation of being able to play this music with the beauty and expertise of the best Klezmer musicians.

The importance of his work to the understanding and appreciation of Polish music was recognized by his receipt of the highest award for civil service from the government of the Polish Republic of Marshall Pilsudski, the Złoty Krzyż Zasługi (Gold Cross of Merit) in 1931.

Ernest was educated in Kraków, graduating from Gimnazjum Św. Jacka in 1922, following which he studied music education at the Pedagogiczny Instytut Muzyczny (Institute of Musical Pedagogy), from which he graduated in 1925. Subsequently, he studied musicology first at the Konserwatorium Towarzystwa Muzycznego (Musical Society Conservatory) from 1925 to1928, and then at the Institut Muzyczny (Music Institute) of Kraków from 1928 to 1929. During these years, he also taught in the secondary schools in Kraków. In 1929, he entered the Jagellonian University, Kraków, Poland to study Philosophy and Pedagogy, graduating in 1932.

Ernest Paul Reiss, 1935.

After graduation, he returned to teaching for another three years, following which he joined the editorial staff of the Katowice newspaper, Polska Zachodnia, as an Associate Editor specializing in musicology and literary affairs. He was also a contributor to the Silesian gazette Powstaniec Śląski, (Silesian Insurgent).

He was particularly interested in increasing the appreciation for Silesian culture by a wider audience. Among his most often quoted reports are those about the legendary Silesian labor activist, playwright, and poet, Maksymilian Jasionowski, whom he visited in 1937.

Editorial Staff, Polska Zachodnia, c. 1938. Ernest Reiss in 2nd Row, Center.

His vivid accounts of that visit, as well as his descriptive declaration of his appreciation for Jasionowski’s poetry were among the source materials cited in a recent a recent critical biography of this figure.8

As the reader already knows, in 1931, while still a student at the University, he met a young American graduate student, Elizabeth Munk Clark, who later had decided not to return to the United States, but to remain permanently in Poland. Their marriage on May 5, 1937, was a step which would dramatically change the course of both their lives in ways they could never have anticipated at the time.

With the planned opening of the World’s Fair of 1939 in New York City, Ernest received the assignment to attend and report on the Fair and, particularly, on the exhibition and activities of the Polish pavilion, for his newspaper. He, and Elizabeth, now pregnant with their first child, were to leave for New York before the end of 1938. Difficulties in obtaining his visa delayed his departure until early 1939. Elizabeth, however, left in time to deliver their first child, Robert, in her hometown of Watertown on December11, 1938.

After his arrival in New York, Ernest’s numerous reports from the Fair described the great pride he felt in being able to report how well the pavilion matched the exhibits of the larger and more wealthy nations. In particular, in one of his early reports, he vividly described the appearance of the entrance to the first hall of the Polish pavilion that was graced by the great statue of King Jagiełło by the sculptor Stanisław Ostrowski. These reports were naturally extremely well received by his Polish readers in Silesia. Original clippings of these numerous articles, together with other memorabilia from the Fair, are now housed in archives of the Pilsudski Institute in New York. The invasion of Poland and the outbreak of the war on September 1, 1939 precluded their return to Poland, at least for the foreseeable future.

The Reiss Family in Kraków after 1939

Ernest’s brother, Tadeusz, and sister, Maria, were both living in Kraków at the outbreak of the war. (Ryszard had died prematurely at the age of 22 in 1927).

On November 9, 1939, two months after the invasion of Poland, Józef, along with some other suspicious faculty members, ignored an invitation to attend the infamous faculty meeting in Collegium Novum with the head of the Gestapo in Kraków, Hans Muller, scheduled by the Rector upon orders from the Gestapo. He thus avoided arrest by the German authorities and subsequent imprisonment in Sachsenhausen, or worse. He sought temporary shelter in the countryside at the home of his wife’s relatives. Following the release of some of the imprisoned faculty from concentration camps in 1940 and 1941, he returned to Kraków, where he remained for the duration of the war. During the war years, it is said that he taught in the underground university in Kraków that had been established in 1942 by the Homeland Government, under the assumed alias of Jan Dembina.9 I have been unable to independently document his participation, although the use of his alias is well known through some his war-time writings.

Maria and her father continued to live in Kraków throughout the war. With the reopening of the university after the war he rejoined the faculty and was appointed a full professor in 1945, retiring in 1953 as professor emeritus. He died in Kraków on February 22, 1956. In the post-war period, his small encyclopedias and textbooks geared to the general public were widely popular. A listing of those publications that have been identified as the most widely held in world libraries, has been published.10 An adaption of this list is appended (Appendix 2). The large number of Józef Reiss’ works and papers, that were left in the possession of the Reiss family, were donated to the University of Southern California for their Polish Music Studies group.

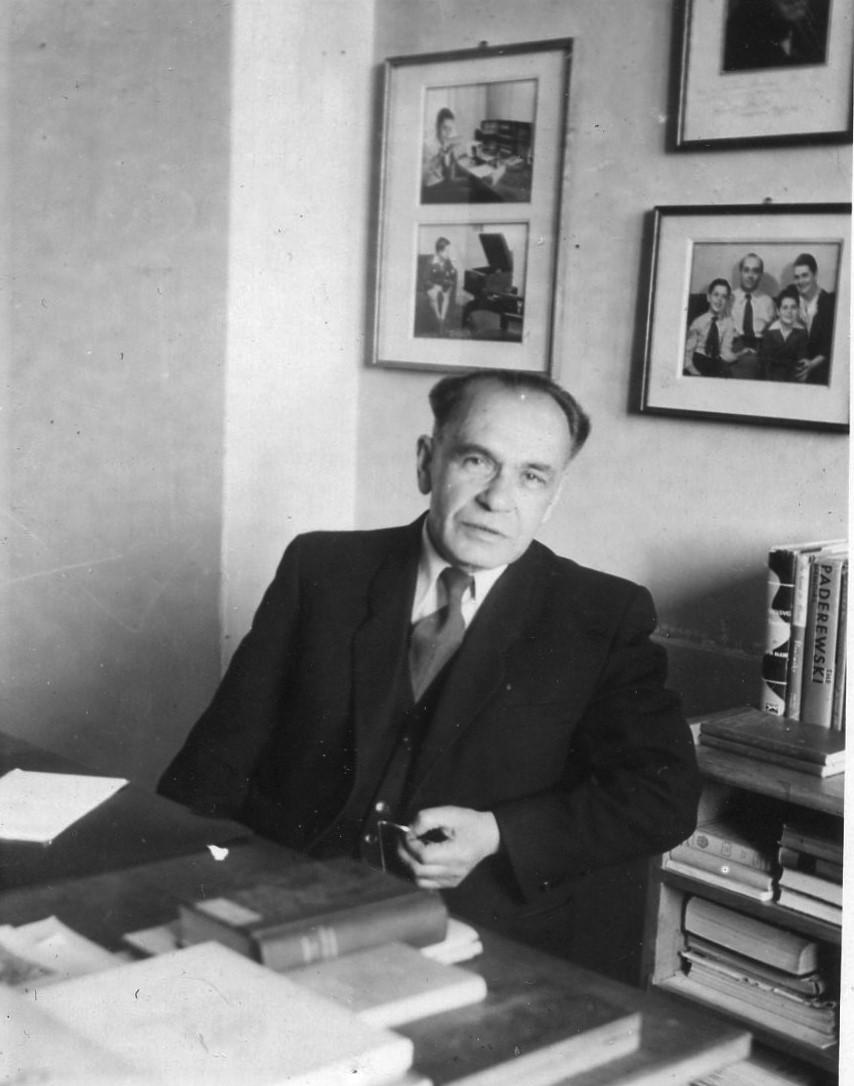

Józef Władysław Reiss, 1948.

In early 1940, Ernest was notified by his father through the German Red Cross that Tadeusz, an officer in the Polish Army Reserve, had been captured and deported to a prisoner of war or concentration camp in Germany. The years spent in the camp left him with physical injuries that remained for the rest of his life. In the closing weeks of the war, he was sent to an internment camp in Sweden where he was kept a prisoner into the immediate post-war period. It was in that camp that he met his wife, Henryka (Henia) Majcherska. They returned to Kraków after the war and, like most others, led a difficult and economically disadvantaged life during the long post-war recovery of Poland.

Tadeusz and Henia had two children. Their first child, Stefan, born on March 11, 1945, later became a successful businessman in Kraków, where he lived in retirement until his death on October 29, 2020. Their second child, Krystyna, was born on May 23, 1947, and showed great artistic talent from an early age. During a visit to Poland in 1958, Elizabeth found her niece to be frail and undernourished. She arranged for Krystyna to come to New York City for the academic year 1961 – 1962, where she attended the neighborhood St. Joseph’s elementary school. In 1963, she was admitted to the Liceum Sztuk Plastyczynch (High School of Fine Arts) in Kraków, from which she graduated in 1967. After having gained acceptance to attend Marymount Manhattan College in New York, beginning in the autumn of 1967, Krystyna had to remain in Kraków, because the Polish government refused to issue her an exit visa.

.jpg)

Henryka and Tadeusz Reiss (Left and right) with Krystyna and Maria, 1964.

In 1970, she graduated, as a fine arts restoration specialist, from the renowned Academia Sztuk Pięknych Jana Matejki (Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts) in Kraków, after the acceptance of her thesis, Konserwacja I Projekt Ekspozycji Obrazu "MAŁA ŚW. RODZINA" z XVII Wieku ze Starego Sącza / Płótno, Conservation and Exhibition Projection of the 17th Century Painting, "LITTLE SACRED FAMILY" from Stary Sącz / Canvas). She married the well-known Kraków painter, Jerzy Witkowski. (Following her marriage, she identified herself as Krystyna Witkowska – Reiss, perhaps to distinguish herself from the acclaimed painter and illustrator, Krystyna Witkowska, born a generation earlier in 1926).

Her achievements, as conservator and copyist, were many. In 1986, for example, she restored the 16th century sculpture, “Pietà,” from the workshop of Wit Stwosz, for the Church of our Lady Help of Christians in Dobcyzce, that a group, led by her husband, had been restoring.11 (Appendix 3) In the 1990s, she continued working on the restoration of artwork and the copying of religious paintings for churches in Kraków and throughout Poland, as well as assisting her husband’s work in the restoration of synagogues in Kazimierz, the ancient Jewish quarter of Kraków. (In 1994, Jerzy accompanied the author on a tour to Kazimierz to describe, in person, the restorations that were taking place).

Tadeusz died in 1983, followed by his sister, Maria, in 1993. Tragically, Krystyna died prematurely at the age of 48 on December 14, 1996 from breast cancer, leaving behind Jerzy, who later was remarried to the artist, Maria Symbórska, and subsequently died in 2012 after a long bout with Parkinson’s disease. Krystyna’s daughter, Anna Witkowska, born in 1975, is currently the university photographer for the Jagiellonian University. Henia continued living in retirement in Kraków until her death in 2007. Krystyna is buried in the famed Rakowicki Cemetery in Kraków, near the other members of the Reiss family.

Krystyna Reiss Witkowska and daughter Anna, c. 1980

The Reiss Family in America – The War Years

Following the outbreak of the war, the family began to establish their new life in the United States. On April 15, 1940, their second son, Stefan, was born. At about the same time, Ernest accepted the position of Assistant Editor, of the New York newspaper, Nowy Świat (New World). Tragically, he was forced to retire from the position only a year later because of the sudden onset of multiple sclerosis, which would, within the space of three years, leave him a paraplegic and confined to a wheelchair. This also precluded Ernest from any consideration of his planned transfer to Canada for subsequent enlistment in the Polish army being reorganized there by the London based Polish government.

In 1941, needing to support her young family, Elizabeth took up the position of Slavic Translator for the United States Committee for the Care of European Children, an organization that had been founded to help care for the anticipated onslaught of refugee children escaping from Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, no escape was possible and thus, there were no refugees for whom to care and the organization went out of existence. Thereafter, the family was divided, Stefan residing with Elizabeth’s family in Watertown to permit her to accept a position as Slavic Secretary at the International Institute in Providence, Rhode Island. It was here that contacts with the Polish enclave in Pawtucket, Rhode Island were established, and which were to be the subject of some of Ernest’s future writings.

In 1944, she left her employment in Providence to take a position with the Polish Information Agency, (an arm of the Polish Government in Exile) in New York City, as Senior Translator for their war-time periodical “Polish Review”. Among her contributions to this publication were her translations of patriotic poetry of leading Polish poets in exile, among them: Josef Wittlin, Stanisław Baliński, and Alexander Janta. (Appendices 4,5).

Of particular interest, she translated and then published her translation of the poem “Battle Song of Warsaw,” following its recitation during the last transmission of the underground Warsaw radio station, Błyskawica, (Lightning) during the Warsaw uprising just hours prior to its discovery and destruction by the Germans on August 24, 1944. (Appendix 6). Finally, she also was able to publish one of her own original patriotic poems based on the legend of the three brothers in which she affirmed her belief in the future freedom of the Polish nation. (Appendix 7). In 1945, at the conclusion of the war, it was she who was asked to prepare the speech to be given by the legendary mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia, on July 15, 1945, on the occasion of his acceptance of the King Jagiełło statue, that had been donated to the people of the United States by the Polish government in exile. That statue, after having remained in storage for the duration of the war following the closure of the World’s Fair, found a new home on the 535th anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald and now resides in New York’s Central Park.

During the war years, the family reestablished their social and cultural contacts with some of their prewar Kraków associates who were now living in the United States, among them and most notably, an old friend, Ludwik Krzyżanowski, (seen in the previous picture of the English club of the Jagiellonian University in 1932). He had come to the United States in 1938 as cultural attaché of the Polish government. He would later become Professor of Polish Studies at Columbia University and editor of the literary journal, The Polish Review. For many years, he was a frequent visitor to the Reiss home.

Ernest and Elizabeth Reiss with Robert and Stefan, 1947.

(This photograph is also seen behind Józef Reiss in the 1948 photograph previously shown).

Ernest continued to contribute articles for a publication relating his views on a variety of musical and cultural trends, as well as some interesting observations regarding life in the Polish enclaves in New York and Rhode Island to the New York literary weekly, Tygodnik Polski (Polish Weekly), and other Polish language newspapers in the United States. Given that his family was living under German occupation, the occasional articles that dealt with more controversial subjects regarding war-time Poland were published under an alias.12

Of particular interest, during the war years, and thereafter, until his death on January 20, 1958, was Ernest’s close relationship with Władyław (Walter) Legawiec, a talented young self-taught Polish-American composer and violinist, who had drawn the attention and assistance of the famous Polish violinist and conductor, Grzegorz Fitelberg, in war time residence in the United States. Ernest wrote extensively about him in one of his 1942 pieces for Tygodnik Polski, regarding life among Poles in the Pawtucket – Central Falls, Rhode Island enclave, entitled "Bardzo zmyślne miasto" (Very clever city). In that article he also described not only for his great admiration for their industriousness and sense of community, but also the patriotism of these Polish Americans for Poland and their sense of duty to Poles fighting for their freedom abroad. (Appendices 8).

Following the Reiss family’s move to New York, Ernest, together with Fitelberg, mentored Walter, who at the time, was also a soldier serving in the American armed forces. Subsequently, and after graduating from the Julliard School of Music in New York, Legawiec attained considerable recognition both in America and Poland, where his works were by performed by the Kraków Opera Orchestra and Chorus and recorded by the Kraków Opera Foundation. Among his most widely hailed compositions were his Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano and his First Piano Sonata that debuted in Carnegie Hall, New York, and was played by the American pianist, Ian Shapinsky. He also wrote a composition to accompany some of the poetry of Pope John Paul II entitled “Easter Vigil” and for which he received a Vatican commendation. He remained close friends with the Reiss family until his death in 2011.

While Ernest and Feitelberg never met in person, Ernest had admired him greatly, since having seen him in concert as conductor and musical director of the Warsaw Symphony Orchestra before the war. During the war years they corresponded frequently, updating each other about Legawiec’s progress. Feitelberg’s letters to Ernest were given to Walter Legawiec in 2001 to be included in his collection of Fitelberg documents. Fortunately, among Ernest’s papers that were left after Elizabeth’s death, was found an annotated draft of a lengthy tribute about Fitelberg, written for publication in a collection of biographical profiles of famous Poles. Included in this tribute was the observation that it was Fitelberg who first brought the music of “Young Poland” to American shores. In his tribute, Ernest also explains that in response to his own hesitant and respectful approaches during their initial interactions, Fitelberg was immediately modest, friendly, kind, and down to earth. Finally, in this tribute, he also reveals that the lessons provided to Legawiec by Fitelberg were absolutely free. (Appendix 8).

The Reiss Family in America: The Post – War Years

Following the war, the family remained in New York City, where they raised their two sons. Initial explorations about the possibility of the family returning to Poland were abandoned, in part because of Ernest’s condition. Except for her completion of a translation of Josef Bliziński’s. "Pan Damazy" (Mister Damazy), together with Professor Noyes, that was then submitted to the U.S. Library of Congress as a manuscript and later made available in e-book form, Elizabeth no longer actively pursued her literary interests.13

She embarked on an entirely new career path in international humanitarian relief, accepting an executive position with the newly formed American Council of Voluntary Agencies, the principle coordinating body for religious and secular relief agencies in the United States that were operating in war-torn Europe and Japan.

In this role, she was instrumental in establishing The Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany (CRALOG) and The Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia (LARA), both of which performed heroic relief work.14 Among the other achievements of the Council was its early role in the formation of the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, now universally recognized by its common name, CARE.

After resigning her position in 1974, she was asked to return to help guide its gradual transition to a structure that would be in accord with the need to address broader worldwide humanitarian problems and the changing American political scene. She remained with this organization in her advisory capacity for several more years. As it became apparent that the Council’s coordinating role for the activities of American voluntary agencies was being supplanted by the American government and that the number of agencies with narrow interests was increasing, a decision was made to gradually phase out its operation, and she was asked to prepare a history of the Council. In her new role, as ACVAFS Historian, the history of the Council was written and published in 1985, a year after the Council had ceased operation.15 As her final service the Council, she collected and organized the historically important documents of the Council, and together with her own relevant papers, arranged their transfer to the Rutgers University library in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Following Ernest’s death and her retirement, Elizabeth continued living in New York near her children and many grandchildren, until her death on February 12, 2001. Following her death, several love sonnets dedicated to her husband and telling of their life together, as well as her annotated war-time translations, were found among her papers. These were subsequently published in a small volume edited by her sons.16 The family’s collection of historically important or rare Polish books and periodicals were donated to the library collection of the Center for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in North Carolina. Neither of their now retired sons, Robert – a physician and Stefan - a physicist, followed in the cultural footsteps of their parents, nor did any of their six grandchildren.

Meeting in Class

by Elizabeth Clark Reiss, c 1960

We often laughed about it later. I,

Newly arrived, an alien student, sat

Huddled in first row alone, to try

To catch the unfamiliar phrases. That

I was conspicuous, I knew. (For who

Sits in front row at college!) Still you came,

Sat down beside me, and the whole class through,

In whispering words and signs you sought my name.

I felt all eyes upon me. Blushing now,

To silence you, I wrote it in a book.

You marveled: whence I came, and why, and how.

I knew not what your words meant, but your look

Translating, vexedly I cast about,

Wondering, my love, why you should seek me out

Endnotes:

1) Stanisław Wyspiański, “Protesilaus and Laodamia,” (trans. Elizabeth M Clark George RNoyes), Slavonic and East European Re view 11, no. 32 (1933): 249-263.

2)Bolesław Taborski,“Polish Plays in English Translations - A Bibliography,”The Polish Review9, no. 3 (1964): 64, 72, 82.

3) Elizabeth M.Clark, “Emerson Dzisiaj (Emerson Today),”Przegląd Współczesny 143 (1934): 443-447.

4)Elizabeth M.Clark,”An American Coed Makes Poland Her Home,” The New American3, no. 7 (September 1936): 2.

5) Elizabeth C Reiss,Personal communication.

6) Małgorzata Wożna-Stankiewicz, “Popularisation of knowledge about Chopin in Kraków and the provinces during the first decades of the 20th century,”Musica Iagellonica 7(2007):177-208.

7) Małgorzata Wożna-Stankiewicz, “Popularisation of knowledge about Chopin in Kraków and the provinces during the first decades of the 20th century,”Musica Iagellonica 7(2007):177-208.

8) Ernest Reiss, Polska Zachodnia 354 (1938):29,(available at on-line at sbc.org.pl); Ernest Reiss.Powstaniec 33 (1937): 21 (available at on-line at sbc.org.pl); Jakub Müller, Maksymilian Jasionowski, Robotnik pióra (Piekary Śląskie, 2019), (available at: https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/439135/edition/410944/content

9) Elizabeth C Reiss, Personal communication.

10) Avaibale at http://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n88624410%20/

11) Elizabeth C Reiss, Architektura i zabytki. Kościół parafialny p.w. M.B. Wspomożenia Wiernych.(Architecture and monuments. The parish church of M.B. Help of Christians) http://dreakmore.tigana.pl/dobczyce/spacer

12) Elizabeth C Reiss, Personal communication.

13) Josef BlizińskiPan Damazy – A comedy in four acts (trans., Elizabeth M Clark and George R Noyes), https://archive.org/details/pandamazycomedyi00blizuoft

14) Eileen Egan and Elizabeth C Reiss,Transfigured Night – the CRALOG Experience (Livingstone Pub Co, Philadelphia,1964); Elizabeth C Reiss,LARA -A Friend in Need (Japanese Ministry of Welfare, 1953).

15) Elizabeth C Reiss, ACVAFS: Four Monographs (New York: ACVAFS, 1985).

16) Elizabeth C Reiss, Reflections in Sonnet Form, eds. Robert F Reiss and Stefan E Reiss (New York, McNally-Jackson Books, New York, 2017).