Neal Pease

“Stop Talking, and Pass the Potatoes”

Neal Pease, historian of Poland and President of the Polish American Historical Association

in a conversation with Marta Cieślak and Anna Müller

Can you tell us a little about your familial background? Where did you grow up? Did your family identify in any particular ethnic or national manner?

I was born and grew up in Lawrence, Kansas in the 1950s and 1960s. Aside from the presence of the University of Kansas, Lawrence was then a smallish typical midwestern town. My family’s ancestral background was almost entirely English and Scotch-Irish, but this was a very distant, scarcely known heritage that had literally no conscious influence on our, or my sense of identity. We would have simply thought of ourselves as basic white-bread “American,” plain and simple.

Did you grow up around any Polish (or Polish American) communities?

There was no Polish or Polonia presence at all in my hometown, apart from a handful of Polish-born professors at KU--who, as I later came to know and appreciate, in those days felt completely cut off from their native culture, apart from each other’s company. As a kid, I happened to make casual acquaintance with some of them, because by sheer chance I became neighborhood or school friends with a few sons of profs of Slavic area studies, so you would cross paths with these Polish academics now and then. Of course, Polishness meant nothing special to me as a youth--I couldn’t have shown you the country on a map--so they didn’t come across to me then as “Polish” so much as simply foreign and exotic, and of no importance to me or my interests. But now, in retrospect, it is tempting--perhaps too much so--to recall these early encounters as somehow predictive of my future career path.

Neal Pease

It’s hardly a secret that historians are often drawn to the fields, in which they specialize, because of their personal experiences or background. You are, above all, a historian of modern Poland but, as you’ve said, you couldn’t “have shown the country on a map” in your youth. How did your journey with Polish history begin? What made you choose Poland as your primary field of study?

Okay, apologies in advance for a lengthy answer, but it’s an odd, roundabout story. In 1970 I was entering my sophomore year at Kansas U., kind of aimlessly majoring in bridge, beer, and bad behavior. A buddy--one of those sons of KU Slavists I mentioned--suggested that I join him in signing up for a class being taught by one of his dad’s colleagues in the History department, and having no better ideas, I said okay, why not? It turned out to be an introduction to Polish and East European history taught by Anna Cienciała, a name you’ll recognize, of course. To my surprise, I found it fascinating, in large part simply because it was so new and unfamiliar to me. Well, Anna spied a faint glimmer of promise in me, I guess, and encouraged me to go on--so I did. As it was, I still would have told you back then that I was more interested in Czechoslovakia than Poland, from having become intrigued by the flowering and blighting of the Prague Spring a couple of years earlier. But at Kansas you couldn’t study Czech, but you could Polish, and so I did; they didn’t have a study-abroad program in Prague, but they did in Poznań, and so I went and spent a year there. By that time, interesting things were starting to happen in Poland, as they would continue to do through the ‘70s, so by then I was hooked. When I began, it was still considered unusual for someone of my Anglo background to turn up in Polish studies; now, not so much any more, of course. But back in the day my non-Polishness was always the first thing that my elders in the field would take note of. I well remember the first paper I delivered at a big scholarly conference, when I was taken to task by a senior Polish-born historian for arguments he found objectionable, making sure to point out to the audience that the offender was a nie-Polak [non-Polish].

Was that kind of, in today’s terms, identity politics something that could have had a discouraging effect on you as a young scholar or did it push you to prove, so to speak, that nie-Polak could study Polish history just as well as someone with Polish background?

I didn’t think of it in those terms. I was simply doing something I found interesting, as if I had decided to specialize in molecular biophysics. Plus, for what it is worth, when I started out, I found my non-Polishness (if that is a word) something of a professional advantage more often than not. That incident at the conference I mentioned was very much an exception. Typically, I would find that Poles were intrigued and pleased that an outsider would have chosen to take a serious interest in their country and its culture. Just to take an everyday-life example, perhaps they were more forgiving of any difficulties I had speaking Polish than they might have had with someone else of Polish background. In my student days in PRL times [Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, or Polish People's Republic, the official name of the Polish state under the communist regime], my Polish or Polish American friends would make me their spokesman in shops, on the theory that the notoriously customer-unfriendly sales clerks might be less surly with the foreign kid. Of course, nowadays no one thinks twice to see a non-Polish surname in the field, and that is a testament to the fact that Polish studies has now gone more mainstream than in the old days.

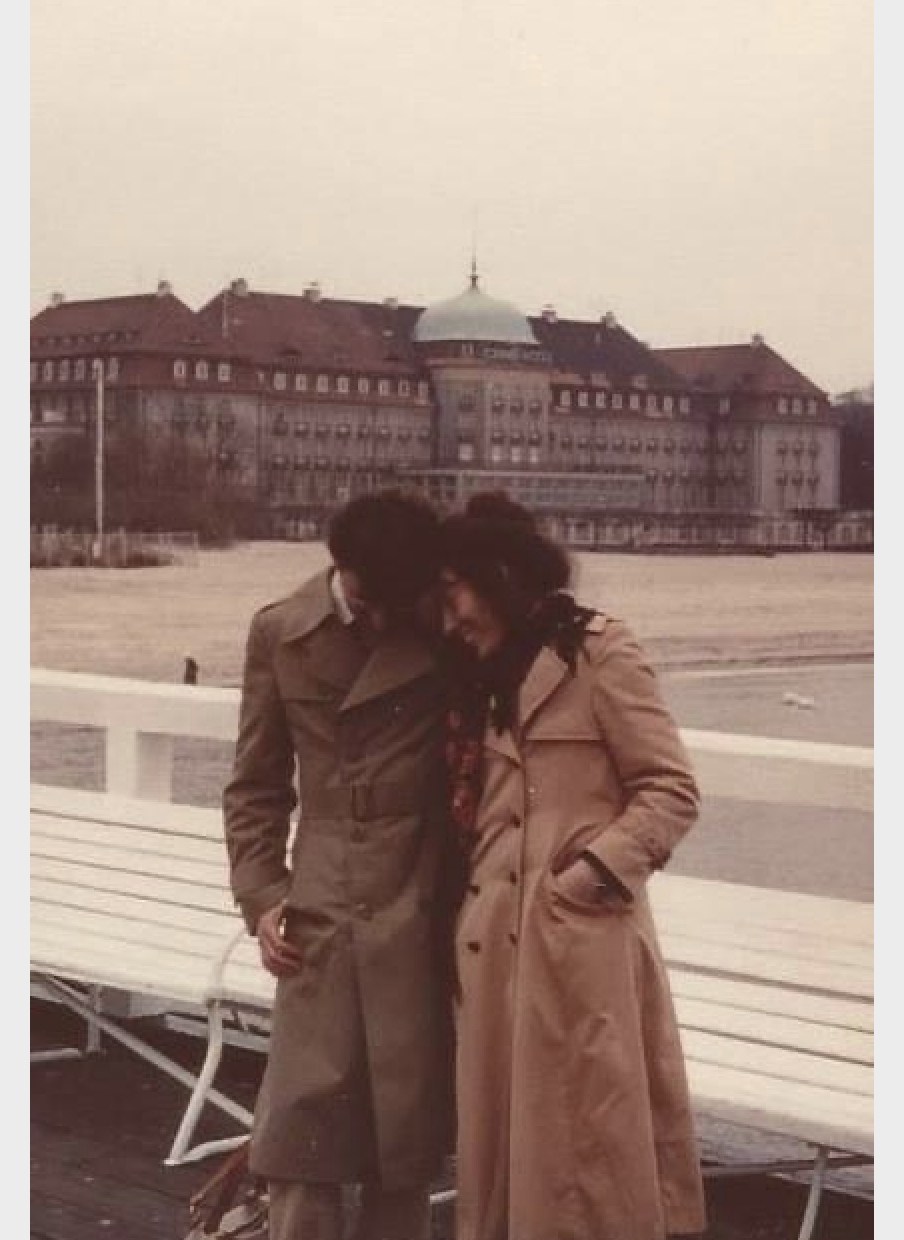

Neal Pease and Ewa Barczyk, Sopot, 1978.

You have published on the history of religion but also on Poland’s diplomatic history, including its relations with the United States. What drew you to these seemingly distinct subjects? Are they distinct in your mind?

One thing that unites them is my interest in the era between the world wars, and of the Second Polish Republic. And I used largely the same skills in both, with a focus on the actions of states and elites, having been trained as an old-school diplomatic historian by first Cienciała at Kansas, then Piotr Wandycz at Yale. As for the choice of subjects? Well, in both cases I took a chance that I could find something useful to say about a topic of interwar Polish history that hadn’t already been said. At the time I became Wandycz’s advisee, he had taken an interest in the subject of the history of relations between Poland and the United States, and nudged me in the direction of doing something along those lines for my dissertation. Then my wife Ewa and I happened to be living temporarily in Warsaw in 1978-1979, while I was carrying out archival research on that very dissertation (and future first book), meaning that we were there when a Polish pope was elected and were able to witness firsthand his famous first pilgrimage to his homeland. This experience made a powerful impression on me, and prompted me to devote much of my subsequent research and publication to the role of Catholicism in the public life of 20th century Poland.

Of course, we need to ask about the place of baseball and generally sport in your life. You have published scholarly work on the history of baseball and the experience of specifically Slavic and Polish American sport figures. You also teach a course on the place of baseball in American history.

What interests me about sport in a scholarly sense is that it can provide vivid and humanly entertaining, but still genuine insights into larger matters of culture, society, and politics. It is generally agreed that few things can tell us more about the civilization of the United States and its sense of identity through the years than the game and industry of baseball. For many parts of the rest of the world, the same can be said of soccer-as-history, and I have taught courses on that subject as well. I have also done a little work on the participation of American Polonia in other sports, such as bowling, boxing, and wrestling, what-have-you.

Neal Pease and Ewa Barczyk

What can the history of sport teach us about the history of a nation, national identity, and nation-building [i.e., immigrants and their descendants finding their place in the American nation through sport]?

See, in the history of the United States, there is a strong connection between immigration and sport: newcomers from other shores arrive with no knowledge of, or liking for American sporting culture or its games, but then the eager adoption of these pastimes by the second and later generations, wanting to “become American,” can give you a useful measure of acculturation. Moreover, immigrants--or more often, their sons--played a notable role in the growth of American professional sports, which classically recruited from the working classes, and didn’t care if your father had gone to Harvard, or if your name was easy to spell or pronounce, but simply asked, can you help us make money by winning this game?

How do you define Polish American, as a scholar of Polish American themes and current president of PAHA? Is this definition in any way affected by the fact that, and we hope you don’t mind us revealing this personal detail, your wife’s parents were post-World War II Polish immigrants in the United States and she herself is a scholar of Polish American studies and an active member and leader of many Polish American organizations?

I’m not sure there is any one-size-fits-all answer to the question of what it means to be Polish American, which can be answered in a variety of ways, and as a matter of subjective self-definition as much as anything else. As someone who considers himself primarily a historian of Poland, who also has a strong interest in the American Polonia, I am pleased to see the recent scholarly tendency to stress the commonalities and connections between the two fields of study. And yes, my wife Ewa--whom I met in Poland when we were both members of the Kansas exchange in Poznań--was born in England, but grew up mostly in Chicago as the daughter of Polish parents unable to return to Poland after the Communist takeover there. While they settled down in America to stay, my parents-in-law always considered themselves Poles living in another country, and kept a Polish household, with the language, the culture, and the customs. In many ways, my admission by marriage into their family became my deepest, most natural and intimate education in a traditionally Polish everyday way of life.

Neal Pease and Ewa Barczyk with PAHA friends, Sopot 2019.

Do you see differences in how various members of your family treat and identify with their Polish American heritage?

Oh, yes. While she considers herself--I think it is safe to say--primarily American, Ewa is very conscious and proud of her Polish heritage. Consequently, we carried over many Polish customs and traditions into our own family life. All of our children have visited Poland at some time in their lives, and all have at least an awareness of their partial Polish heritage. The “partial” reference reminds me of a story: at one time, at the family dinner table, I was yammering on about some aspect of Polish this or that, in full know-it-all mode. At one point, our younger son, having heard enough of this, reminded me that, by the laws of genetics, I was the only one present who was not Polish at all, so could I please stop talking, and pass the potatoes? Twenty years later, I’m still looking for a good retort.