by Vivian Reed

On April 2, 1918, Gibson continued his conversation with Horodyski from Paris where we left off last week:

“… That brought him to the question of getting propaganda done for us by the Vatican.”

On April 2, 1918, Gibson continued his conversation with Horodyski from Paris where we left off last week:

“… That brought him to the question of getting propaganda done for us by the Vatican.”

For predominantly Catholic Poland, the Vatican had been a significant power over her centuries of varied political status. Until this point in time, Horodyski considered Vatican support for Poland negligible – and he wanted to change that! Because of his work with British (and now American) intelligence, Horodyski had a unique insight into the inner workings of Vatican relations. And because of his high connections, he had access to powerful players in the field of Vatican politics.

According to Horodyski, “German and Austrian representatives at the Vatican are sitting up in Switzerland and communicating thru their diplomatic bags which pass uncensored” by Allied or imperial intelligence. This left the Allies, and the Polish cause, at a disadvantage. According to Horodyski:

“The Vatican, according to this good Catholic, is merely a big business concern and the Boches have played the game according to the rules, spending huge sums in masses and generally making themselves good customers. Each of the Cardinals has the distribution of certain funds, foundations, incomes, etc... So far the Boches have had the monopoly of this sort of thing and H. thinks we ought to get to work and try to corner a little business for ourselves. If this were done for a little time and it was made clear that the United States was important to the Church he believes it might be possible to stir the Pope out of his neutrality (for he believes that he is not pro-Boche) and get him to send a few blasts into Germany.”

For that to happen, Horodyski planned to correct the sad state of affairs that “the Allied cause is very poorly represented at the Vatican.” He had definite opinions about some of the current representatives:

“De Salis, who is the British representative, is stupid and without influence. Carton de Wiart is the Belgian and has apparently harped so much upon the sorrows of his unhappy country that everyone flees when they see him coming, - so he is less than no help at all. None of the other allies is represented at this time. The Boches have their men in Switzerland, very active and with freedom of communication. The late Spanish representative was intensely pro-Boche, but H. did not know about the new man. Being something of a misanthrope he was inclined to believe on general principles that this one is also a bad egg.”

This all led down to the idea that the United States should be represented in some form at the Vatican. That we should pick out some impressive gentleman, preferably not a Catholic, who would give an idea of culture and friendliness but at the same time have a lot of force, - an easy man to find. He need not be regularly accredited but could be sent to settle some pending matter and allowed to remain for an indefinite time. …”

Before the end of the month, Gibson and Horodyski would arrive in Rome, meeting these very persons, as well as many others, and make a start at enacting the plan.

After presenting his plan to have the US represented at the Vatican, Horodyski turned his attention to the Supreme Council. A Supreme War Council, which ran a centralized command of Allied forces, was actively functioning since November 1917. But Horodyski believed that another step was necessary:

“that we establish somewhere on this side of the water a Supreme War Council for Diplomatic and Political questions. Now all matters have to be referred to London, Paris, Rome, Washington, Tokyo, Havre, Corfu, Lisbon and the Lord knows where else and the interchanges of views waste a shameful amount of time, so that when a decision that would have been right is eventually taken it is no longer suited to changed conditions.”

Horodyski is for having each of the nations concerned, at least the more important of them, establish a representative at Versailles just as has been done for the Supreme War Council, a man with nothing to do but decide questions in constant discussion with the people on the ground.”

While Horodyski worried that the British might be opposed to the idea at first, Gibson was sure “that everybody would be opposed to it at first and from that time on until after some years more of war we are driven into it as we were driven into the Supreme War Council.”

By the end of this meeting, Horodyski startled Gibson by turning clairvoyant:

“Horodyski says that during the next four to six weeks he thinks I will have great influence on Washington, that after eight weeks they will pay little to no attention to me and that at the end of three months he will not want to bother with me unless I have proved my intelligence by starting for home. He evidently exaggerates the importance of my mission but no words of mine can convince him that I am not the GREAT WHITE HOPE.”

Horodyski’s prediction underestimated the influence Gibson would have over the rest of his career!

Biographies:

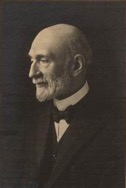

John De Salis, 7th Count de Salis-Soglio (1864-1939) was a British diplomat whose career stretched from 1887 through 1923. His last post was that of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary on a special mission to the Holy See, 1916-1923.

Carton de Wiart presents a problem. The Carton de Wiart most often associated with Poland, and the closest in professional interests to Horodyski, was British Army officer Adrian Carton de Wiart (1880-1963). However, Adrian was not the Belgian representative to the Holy See in 1918, nor could he have been due to his war activities and injuries. The honor belonged to Jules van den Heuvel.

John De Salis

Jules van den Heuvel (1854-1926) was a Belgian who held doctorates in both law and political/administrative sciences, taught at the University of Ghent, and served as Minister of Justice 1899-1907. In 1914, he drafted the Belgian reply to the German Ultimatum preceding the invasion in August. Van den Heuvel served as Belgium’s Minister Plenipotentiary to the Holy See from 1915 to 1918. When the war was over, he drew up a list of damages suffered by Belgium for the Paris Peace Conference and was active on the Reparations Commission.

The late pro-German Spanish representative and his replacement remain unidentified.

Jules van den Huevel

Please look for the next post when Gibson explores Rome and begins to meet with officials - Polish, Vatican, and others. Until then, stay well and thrive!

Vivian

Links and documentation:

About Adrian Carton de Wiart: http://abmms.be/article1.html

About Jules van den Heuvel: https://peoplepill.com/people/jules-van-den-heuvel/

About Polish-Vatican relations:

Neal Pease, “Poland and the Holy See, 1918-1919,” Slavic Review (Autumn, 1991, Vol. 50, No. 3) Cambridge University Press, pp. 521-530. JSTOR